Ben Harney, sometimes called the "Father of Ragtime," was one of the first entertainers to put ragtime on the stage in legitimate theater and Vaudeville. Many also consider him the first to have corrupted either white music with a black form, or the black ragtime music in its adaptation into a white entertainment. Whichever may be true, he did introduce ragtime to a large segment of the white population, giving it the legs necessary to grow into a full-fledged genre sooner than it might have otherwise. He did not consider himself the genre's father, but rather its adoptive parent.

Harney was born to Benjamin Mills Harney and Margaret Wellington Draffen in Kentucky. The exact location has been disputed, even in official records, because he was supposedly born aboard a steamer (as per his 1897 marriage license) on the Mississippi River. Picking the closest town of origin has resulted in guesses including Louisville or Middlesboro in Kentucky, and even Nashville or Memphis in Tennessee. Memphis is listed on his father's military pension form, accepted by the family as most likely. Wherever it was, and it appears to have been a birth in transit, Louisville was considered to be Harney's home town. The year of birth is commonly shown as 1872, but the 1880 census, taken in June after his birthday, stated that he was 9 years old, suggesting an 1871 date instead. To further reinforce this, there is no draft record in 1917 or 1918 for Harney, which would have been a requirement if he were born in 1872 or later. While neither of these are definitive proof of his year of birth, they are still consistent. In general, earlier census records on most composers have proven to be the most reliable in terms of an accurate year of birth, so 1871 is the more likely year in this case.

Harney's race has also been called into question, including the possibility of some mix. The family's own genealogical research indicates, however, that he was of white heritage for many generations on both sides. His last wife, Jessie, had written that Ben's great uncle, General Selby Harney, was of Louisiana Creole extraction, but again the census records indicated otherwise. Eubie Blake's comments about him being a black passing for white were later negated when he admitted to historian Ed Berlin that he had not actually met Harney. Willie "The Lion" Smith had the same opinion. To the contrary, it was stage entertainer (not the Detroit ragtime composer) Fred Stone who commented in 1924 that Harney was "a white man who had a fine Negro shouting voice."

Ben's father, a Captain in the Civil War, was a civil engineer, so the family lived comfortably in Louisville during the Reconstruction era. He was also, according to notes left by Jessie, fairly proficient in both mathematics and music. It's not clear what happened in the next few years, but in the 1880 census Margaret appears to have been divorced or divorcing from Benjamin as mother and son are living with her father, lawyer and state legislator John Draffen, in Anderson County, and she had retained her maiden name. Reports vary on whether Ben took some formal piano lessons over the next few years and learned the classics or whether his mother taught him the fundamentals by rote. Either way he did have some musical knowledge and experience at the keyboard.

When he was 16 he was reportedly sent to a military academy (there is at least one dispute to this story - it may have been just a boarding school) in Middlesboro (another clue to support his being of white descent since blacks could not attend at that time). While there he had a job at the local Post Office to support his expenses, possibly starting in 1888. It was there that he was exposed to the strains of white Cumberland Mountain musicians playing syncopated folk tunes on a long-necked fiddle using a banjo tuning. Even though the players were not black, their playing seemed to evoke that of Negro musicians of the south. (In truth, in spite of his claims, that area of Kentucky and Virginia had a healthy black population, so he was also likely exposed to their playing as well.) Within a couple of months of having heard this music continuously, Ben was hard at work trying to write down these "broken rhythms" in his own compositions. He then started to add words in what he considered a "darkey dialect," even though he had little direct exposure to this. One of these early tunes, which his last wife insisted after his death that he claimed to have written in his teens, was called You've Been a Good Old Wagon but You've Done Broke Down, completed perhaps before even 1889. By 1890 he was the assistant postmaster of Middlesboro and in July joined the Kentucky National Guard.

|

It is possible, but not easily established or verified, that Harney was briefly married while in Middlesboro. Mention of his marriage to a young Kentucky girl named Jessie Boyce was made to historian Rudi Blesh by Bruner Greenup, a Harney acquaintance. Historian William Tallmadge[1] postulates that since Harney was living for a time next door to his father that Greeenup's story may be true. Marriage and census records have not turned up anything conclusive, and the closest match would be a Bessie Boyce, who would have been around 15 at the time of the alleged marriage in 1891. They would have split in 1893, but subsequent records of Bessie do not indicate a prior marriage. If true, this makes more sense than the possibility that his last wife, Jessie Haynes, was also named Jessie Boyce at some point.

In an April 1916 article about Harney in the Lynn, Massachusetts Evening News, it was written, "Instead of the negro for his pupils and audience, as the nature of the songs would rather make one think, Harney used to entertain the moonshiners with his rag-time music. When the makers of illicit whiskey were not busy killing off a Deputy Sheriff or getting their stills in working order, they would cluster around Harney in some popular place and listen to his rather musical selections. As these songs were just being created by Harney, they made a tremendous hit with the natives, and whenever he would start the piano, a thumping out of one of his go-band songs, business in the immediate vicinity would be suspended and Harney would own the place until he got tired." This is rather lavish, and possibly a planted publicity story, but it does at least give some idea of the environment in Middlesboro at that time.

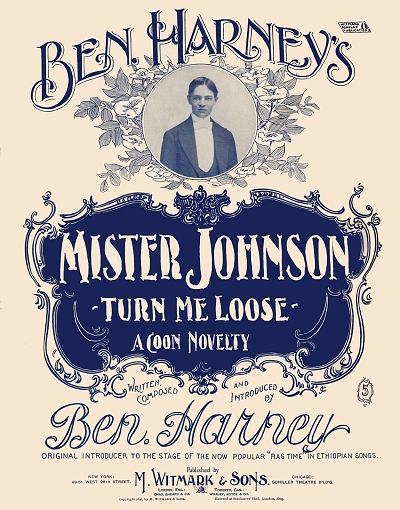

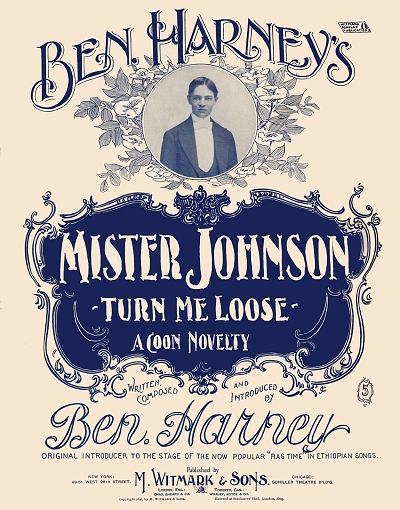

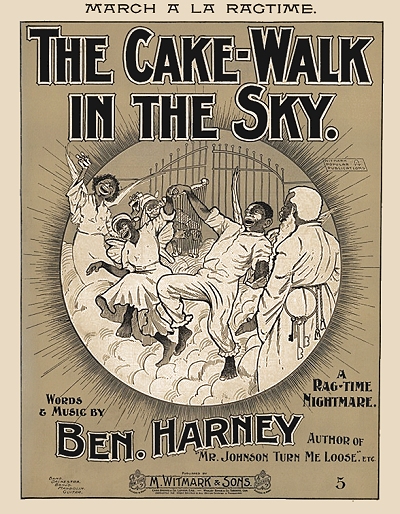

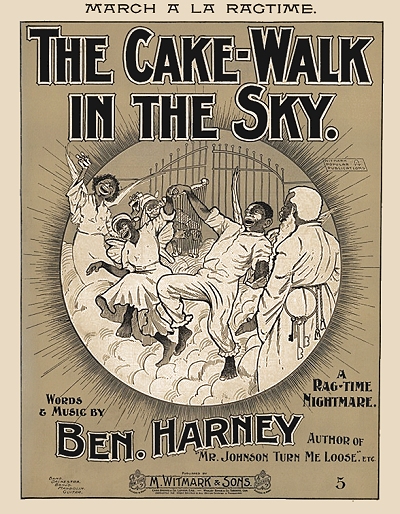

In 1893 Harney quit his postal job and returned to Louisville to pursue music. There was also a lot more exposure at this time to developing black music styles in this more urban setting. Forming a group with some of his musician friends, he plied the venues in Louisville playing dance music, but always with an ear towards syncopation. It was said that the red-haired youth sang out with a husky voice, often in a pseudo-Negro dialect, tap danced both standing and sitting, and used a cane to supplement his rhythms, some saying it acted as a third leg in some ways. He still relied on a "day job" for a while, working as a lithographer for Macauley's Theater in Louisville. Harney became quite popular in Louisville and soon was able to get some of his work in print, including Good Old Wagon, with the help of a local businessman. In 1895 he hit the road and Ben concentrated in theaters in the East and Midwest, reportedly having little trouble getting work for a few weeks at a time.He finally tried for New York City in late 1895 or early 1896, with his growing reputation succeeding him. Ben also brought his latest "rag-time darkey" song with him, Mister Johnson. Some writers considered this to be the first piece published in the blues genre, but that point is debatable since it may reflect the feeling of the blues lyrically, but not musically.

Harney became quite popular in Louisville and soon was able to get some of his work in print, including Good Old Wagon, with the help of a local businessman. In 1895 he hit the road and Ben concentrated in theaters in the East and Midwest, reportedly having little trouble getting work for a few weeks at a time.He finally tried for New York City in late 1895 or early 1896, with his growing reputation succeeding him. Ben also brought his latest "rag-time darkey" song with him, Mister Johnson. Some writers considered this to be the first piece published in the blues genre, but that point is debatable since it may reflect the feeling of the blues lyrically, but not musically.

Harney became quite popular in Louisville and soon was able to get some of his work in print, including Good Old Wagon, with the help of a local businessman. In 1895 he hit the road and Ben concentrated in theaters in the East and Midwest, reportedly having little trouble getting work for a few weeks at a time.He finally tried for New York City in late 1895 or early 1896, with his growing reputation succeeding him. Ben also brought his latest "rag-time darkey" song with him, Mister Johnson. Some writers considered this to be the first piece published in the blues genre, but that point is debatable since it may reflect the feeling of the blues lyrically, but not musically.

Harney became quite popular in Louisville and soon was able to get some of his work in print, including Good Old Wagon, with the help of a local businessman. In 1895 he hit the road and Ben concentrated in theaters in the East and Midwest, reportedly having little trouble getting work for a few weeks at a time.He finally tried for New York City in late 1895 or early 1896, with his growing reputation succeeding him. Ben also brought his latest "rag-time darkey" song with him, Mister Johnson. Some writers considered this to be the first piece published in the blues genre, but that point is debatable since it may reflect the feeling of the blues lyrically, but not musically.The first mention of Harney in Manhattan is found in February, 1896 when he was playing at the famed 14th Street theater of Tony Pastor, the most prominent vaudeville venue at that time, which also took in a young Mike Bernard within a few months as a star attraction. The classically trained Bernard claimed he got his interest in ragtime from hearing Harney play, and quickly followed Harney's lead. Pastor was experimenting with the notion of "continuous Vaudeville," acts rotating at almost any hour of the day, a topic which made for a funny Vitaphone short in the 1920s. A February 1, 1896 review in the New York Clipper notes that his act was polished and well balanced, and that his dialect singing was "a worthy copy of the subject he mimics." A February 22, 1896 review in the same paper said that Harney "jumped into immediate favor through the medium of his genuinely clever plantation negro imitations and excellent piano playing." A week later he received similarly kind reviews appearing at B.F. Keith's theater in Manhattan.

It wasn't long before Mister Johnson (Turn Me Loose) was published and being performed around town. He also soon teamed up with a black ragtime performer from Tennessee named Strap Hill, who worked with Harney on and off for several years. On New Years Day 1897, Harney married Canadian-born singer/actress Edyth Murray in Streator, Illinois. This was, of course, the year that ragtime - in both song and piano rag form - broke out across the country. Pastor and other Vaudeville bookers kept Harney very busy, and by the end of the year he was consistently billed as "The Inventor of Rag-Time." This claim was helped along to some extent by the release of Ben Harney's Ragtime Instructor, which was actually edited by composer/arranger Theodore Northrup, originator of what many consider to be the first true piano rag in February of 1897, Louisiana Rag: Pas Ma La.

By 1898, Harney had helped to make the word "rag-time" (not just "rag") well known not only in New York but beyond. He has sometimes in retrospect been one of many entertainers criticized by blacks for bastardizing what was considered to be their original music, although in fairness it appears to be more likely that he adapted what he had learned from both white and black musicians. However, many white musicians felt he was corrupting himself by performing "darkey toons" without the usual camouflage of burnt cork on his face. Rumors persisted, even beyond his death, that there was some Negro blood in him, or if he had not been seen in person, that he was likely black. Yet Harney persevered, and countered the establishment in one way by doing something very unlikely, and not widely practiced. He hired black musicians to work with him. Whether this was to authenticate his presentation or simply deflect some of the criticism is unclear. But it was a pioneering effort in any case. He still had to have white musicians with him in some venues as many places would refuse to hire any mixed groups. Harney was part of a benefit concert in the early 1900s at the Metropolitan Opera House in Manhattan, doing his now famous "stick dance" with the cane, on the same program as more serious stars like Lillian Russell. In a sense, even if tainted by racial bias, these types of appearances helped bring legitimacy to ragtime in white society more so than any black performer in that decade might have been able to do, including the highly talented Bert Williams during his time with the Ziegfeld Follies, simply because of the social climate of the age.He continued to get praise in the press as well, with one article in a New York paper citing that he could "sustain certain notes for special effect to extravagant, breathtaking lengths; others he would break in a way that he alone could manage."

But it was a pioneering effort in any case. He still had to have white musicians with him in some venues as many places would refuse to hire any mixed groups. Harney was part of a benefit concert in the early 1900s at the Metropolitan Opera House in Manhattan, doing his now famous "stick dance" with the cane, on the same program as more serious stars like Lillian Russell. In a sense, even if tainted by racial bias, these types of appearances helped bring legitimacy to ragtime in white society more so than any black performer in that decade might have been able to do, including the highly talented Bert Williams during his time with the Ziegfeld Follies, simply because of the social climate of the age.He continued to get praise in the press as well, with one article in a New York paper citing that he could "sustain certain notes for special effect to extravagant, breathtaking lengths; others he would break in a way that he alone could manage."

But it was a pioneering effort in any case. He still had to have white musicians with him in some venues as many places would refuse to hire any mixed groups. Harney was part of a benefit concert in the early 1900s at the Metropolitan Opera House in Manhattan, doing his now famous "stick dance" with the cane, on the same program as more serious stars like Lillian Russell. In a sense, even if tainted by racial bias, these types of appearances helped bring legitimacy to ragtime in white society more so than any black performer in that decade might have been able to do, including the highly talented Bert Williams during his time with the Ziegfeld Follies, simply because of the social climate of the age.He continued to get praise in the press as well, with one article in a New York paper citing that he could "sustain certain notes for special effect to extravagant, breathtaking lengths; others he would break in a way that he alone could manage."

But it was a pioneering effort in any case. He still had to have white musicians with him in some venues as many places would refuse to hire any mixed groups. Harney was part of a benefit concert in the early 1900s at the Metropolitan Opera House in Manhattan, doing his now famous "stick dance" with the cane, on the same program as more serious stars like Lillian Russell. In a sense, even if tainted by racial bias, these types of appearances helped bring legitimacy to ragtime in white society more so than any black performer in that decade might have been able to do, including the highly talented Bert Williams during his time with the Ziegfeld Follies, simply because of the social climate of the age.He continued to get praise in the press as well, with one article in a New York paper citing that he could "sustain certain notes for special effect to extravagant, breathtaking lengths; others he would break in a way that he alone could manage."Sometime around 1900 or 1901, Harney met the woman who would become his final wife, Jessie Haynes. The lady singer had been featured on the cover of one of his 1901 songs, which was dedicated to her. Ben and Jessie formed their own Vaudeville act with singing and dancing, often in blackface, and toured the U.S. on the Keith and Orpheum circuits, and the world on other tours over the next decade and more. One somewhat scandalous number performed by the white Jessie was Harney's I Love One Sweet Black Man, creating a stir from time to time when they toured. Harney also wrote and produced an all-black variety show called Ragtime Reception, although there was some attrition of his New York musicians once James Reese Europe and his Clef Club started dominating black-based entertainment in the city in the early 1910s.

Until Al Jolson's rise on the stage in the mid 1910s, Harney was possibly the highest-paid male entertainer in show business. It is unclear when and if Harney was divorced from Edyth, but it appears that he and Jessie married sometime between late 1915 and mid-1916. The couple appears to never have had any children. However it was also clear that the Harneys were often far from frugal, generous and capricious in their spending, and when work started to dry up this became an issue. Ben's last composition in 1914, Cannon Ball Catcher, made it only into a vanity press, and did not see distribution.

As the jazz age approached, the aging Harney was not able to adapt his singular style in a way that would readily fit into the trends of the newer and more progressive music forms.

|

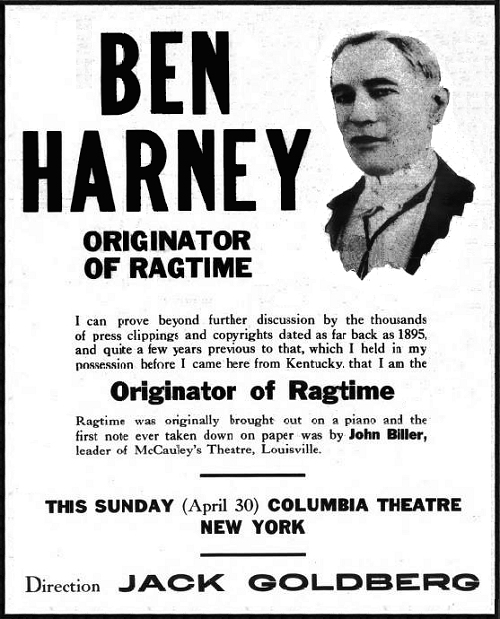

The question of Harney's role in the origination of ragtime was noted in a 1916 snippet in the Music Trade Review. "The Review Hears: That the question as to who originated ragtime has again come to the fore with Ben Harney and McIntyre & Heath, as rival claimants. That Jim McIntyre claims his 'Rabbitt' [sic] song of 1897 was the first ragtime, while Harney has $100 which says that his 'Mister Johnson Turn Me Loose' was the first. That present day writers are not worrying so much about who originated ragtime as about to whom they are going to sell their latest number." This item clearly stated that any answer to this question was being couched with a "so what" attitude, another indication that ragtime was on the way out. In the end, it was clearly Harney that would be remembered.

Bookings declined rapidly in 1917 and 1918, and the Harneys had to scale back their lifestyle and their act. The couple continued to tour in Vaudeville and on their own in the 1920s, although his billing as the originator of ragtime carried almost no weight during this time. They were likely viewed as a quaint reminder of a different generation. His obituary in Variety suggests that they largely retired from touring on the Orphuem circuit in late 1923. Although Harney was largely ignored by commercial record companies, one archivist managed to get a few sides of his unique vocal stylings on disc in 1925. Of of the better venues for the couple, they were frequently in Indianapolis, Indiana, Chicago, Illinois and Detroit, Michigan, still performing on occasion, often in blackface. While it seems out of vogue for the 1920s, stage veterans Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor and George Jessel among others still donned burnt cork frequently as well.

Ben suffered a heart attack in 1928 and the Harneys had to greatly curtail any subsequent performance activities. They were found in Detroit in 1930 where the enumeration listed the couple as Mr. and Mrs. Ben R. Harney, actor and actress, temporarily lodging in a boarding house as the couple had likely settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by this time. There were periods in the late 1920s and early 1930s when some nostalgia for ragtime emerged, particularly after the release of Warner Brothers sound film The Jazz Singer, and they found work billed as early jazz singers in some venues. Philadelphia was close enough to New York City for them to commute just in case they were called back into action during the era of sound films. But the Great Depression and his health issues all but removed their viability as performers. They lived simply on pensions from the Actor's Fund, and reportedly did not have a piano in the home. So it was in relative poverty in Philadelphia that the once highest-paid entertainer and "originator of ragtime" was felled by a heart attack four days short of his 67th birthday. He was interred at Fernwood Cemetery in Delaware County, Pennsylvania.

There was a small obituary in the New York Times in addition to the one in Variety, but he still remained all but forgotten. Jessie still talked proudly about her late husband in interviews for articles and eventually to Rudi Blesh for the first book on the era, They All Played Ragtime. Circumstances of her death, years later, were questionable. She was reportedly found slumped in a chair with a gas jet on in the room, which was officially deemed to be accidental, although the landlord had made some indication to Blesh that it may have been a suicide. In historical perspective Harney can once again be remembered, perhaps as the man who introduced ragtime music to much of white society, even if not quite its originator.

The Harney Family has done some great genealogy on their famous relative, from which part of this biography was compiled. In addition to efforts in finding early and later census records (he appears to have been missed in 1900 and 1910) by this author, additional definitive work was also done by ragtime historian Dr. Edward Berlin and historian Lynn Abbott. There are still questions on aspects of Harney's life as conveyed in his own interviews, but this represents what is known to be the most accurate information, except where noted when called into question. Historian Fred Hoeptner made the connection with Bessie Boyce, who may yet be a person of interest in this story.

1. Ben Harney, The Middlesborough Years 1890-1893, William H. Tallmadge, American Music Journal, University of Illinois Press

Compositions

Compositions