Caroline May "Carrie" Bruggeman Stark (May 1, 1881 to June 29, 1972) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1903

Dainty Foot: Dance CharacteristicDainty Foot: Schottische [Same as above?] 1904

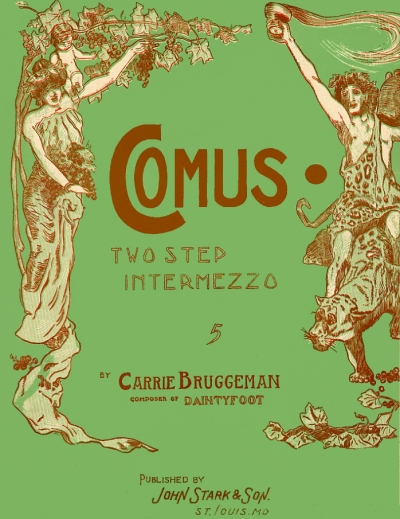

Comus: A Two-Step Intermezzo1908

The Dream Pillows: Lullaby [1]1912

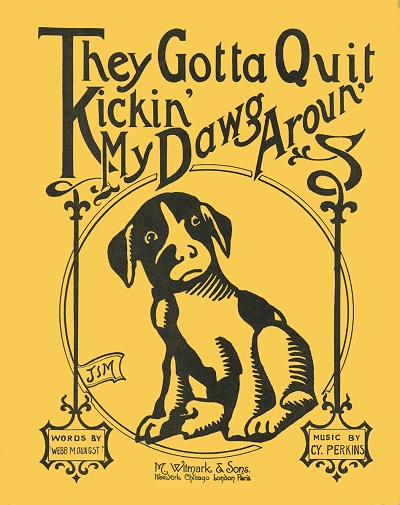

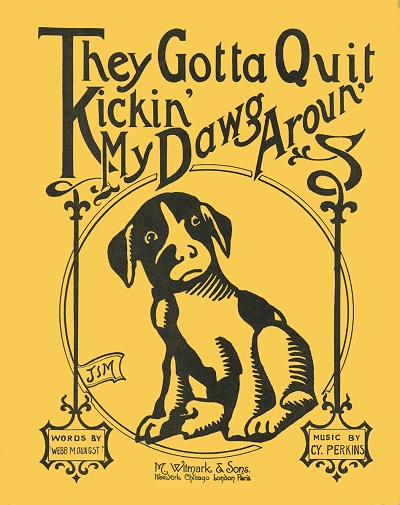

They Gotta Quit Kickin' My Dawg Aroun' [2,3]1914

Tango Tangle [1]Sunset Waltz [1] |

1917

Baby Blues (Fox Trot) [1]Baby Blues (Song) [1,4] Unknown or Uncertain

Slumber Time

1. as Cal Stark

2. as Cy Perkins 3. w/Webb M. Oungst 4. w/Margie Brandon |

One of the more cryptic composers in ragtime was actually related by marriage to one of the most eclectic ragtime publishers, and she would manage to find her own place in the history of the genre, albeit leaving a bit of controversy in her wake. Caroline May Bruggeman was born in Alton, Illinois, just north of Saint Louis, Missouri, the only child of tailor Adolph Bruggeman and his wife Mary "Mattie" Carter. Just over a year before her birth Adolph appeared as single in the April, 1880, Federal census taken in Alton, so her parents were likely married within a year of her birth.

Caroline May Bruggeman was born in Alton, Illinois, just north of Saint Louis, Missouri, the only child of tailor Adolph Bruggeman and his wife Mary "Mattie" Carter. Just over a year before her birth Adolph appeared as single in the April, 1880, Federal census taken in Alton, so her parents were likely married within a year of her birth.

Caroline May Bruggeman was born in Alton, Illinois, just north of Saint Louis, Missouri, the only child of tailor Adolph Bruggeman and his wife Mary "Mattie" Carter. Just over a year before her birth Adolph appeared as single in the April, 1880, Federal census taken in Alton, so her parents were likely married within a year of her birth.

Caroline May Bruggeman was born in Alton, Illinois, just north of Saint Louis, Missouri, the only child of tailor Adolph Bruggeman and his wife Mary "Mattie" Carter. Just over a year before her birth Adolph appeared as single in the April, 1880, Federal census taken in Alton, so her parents were likely married within a year of her birth.Carrie claimed that she had very little musical training, and mostly played by ear. However, she obviously had taken enough lessons that she was able to read music sufficiently, and it landed her a job at the Boston Department Store in St. Louis in the late 1890s as a sheet music demonstrator, a position commonly held by women in the Midwest and eastern United States. It was there that she met William Paris Stark, the son of music store owner and fledging publisher John Stillwell Stark, in 1899 or 1900, around the same time that the senior Stark had taken on Scott Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag for publication and distribution. Will handed her a copy and asked if she would learn the piece and plug it. She worked hard to do so, and in her own words, "began pounding it out at work as often as I dared."

As of the 1900 enumeration Carrie was still living with her parents, with Adolph listed as a garment cutter. The family also had two boarders residing with them. Even though she was employed part time as a pianist, Carrie did not have any occupation listed. While she claimed that Will kept visiting her at the store until he eventually proposed marriage, in reality, the couple was not married until Christmas Day, December 25, 1904.

In the interim, Carrie not only started learning more rags and songs, but writing them as well. One of the first of her instrumentals to be published under the Stark imprint was Dainty Foot, released under the subheadings of a "dance characteristic" and a "schottische," but very possibly the same work. This was followed by an almost-rag the next year, Comus, probably the last one issued under her own name. It was named for the Greek god of Festivity (and excess), Comus, a son of Bacchus.

Then for a while she was busy with marriage and babies, giving birth to John S. Stark around 1906 and Ruth C. Stark in late 1907. Her next piece in 1908 would appropriately enough be a lullaby, most likely written for her children, and perhaps the first of her pieces published under the opposite gender pseudonym of Cal Stark. As of the 1910 census William was listed as a music publisher, but Carrie showed no occupation. The couple was hosting Carrie's mother, who had been widowed early in the decade, and her stepfather, William Peters,, who had married her mother around 1906.

Carrie herself admitted to not being able to notate her own works, and that she had allegedly written more songs than she could even remember, although very few of them actually made it into print. That which did get published was usually completed by her brother-in-law, the resident musician of the company, Etilmon Justus "Til" Stark, who also had several compositions in his own name in print. She would play the piece for him and he would notate it for typesetting and production. But there was at least one exception to this, which was her next act, a hard one to follow.

That which did get published was usually completed by her brother-in-law, the resident musician of the company, Etilmon Justus "Til" Stark, who also had several compositions in his own name in print. She would play the piece for him and he would notate it for typesetting and production. But there was at least one exception to this, which was her next act, a hard one to follow.

That which did get published was usually completed by her brother-in-law, the resident musician of the company, Etilmon Justus "Til" Stark, who also had several compositions in his own name in print. She would play the piece for him and he would notate it for typesetting and production. But there was at least one exception to this, which was her next act, a hard one to follow.

That which did get published was usually completed by her brother-in-law, the resident musician of the company, Etilmon Justus "Til" Stark, who also had several compositions in his own name in print. She would play the piece for him and he would notate it for typesetting and production. But there was at least one exception to this, which was her next act, a hard one to follow.There was a stir caused in 1911 and 1912 that was literally a matter of politics. Carrie wrote a song, (some insist she adapted an already existing tune from the Sally Ann family) with Iowa-born newspaper printer and editor Webster Mil (Webb) Oungst (1854-1943). The song They Gotta Quit Kickin' My Dawg Aroun' was arranged by John Stark's staff arranger and composer Artie Matthews and published by Carrie's father-in-law. It nearly immediately became known as the official theme song for the Presidential Campaign of Missouri's favorite son James Beauchamp "Champ" Clark. It is somewhat likely that Oungst submitted the clever lyrics to publisher Stark in hopes that it could be set to music, and since Will was managing at that time, he had Carrie step in to plug in the melody. Mrs. Stark claimed that she chose the pseudonym of Cy Perkins because it sounded like a "good hillbilly name, and might make the music sell better." Candidate Clark actually had a nice lead going, and this may have also been the motivation for Carrie to use the the Cy Perkins name in order to avoid any controversy as a woman songwriter involved in a political campaign.

In any case, the piece was known even before it was officially published by Stark, having been used in a rally in December of 1911. The Dawg song became so popular that publisher M. Witmark and Sons in New York City wanted it for their own catalog. They offered John Stark the respectable sum of $5,861.37 to acquire the piece and the plates, plus any unsold copies to date, which was soon accepted. The copyright date for Stark Music was January 3, 1912, and Witmark recopyrighted it on March 7.

However, soon after this the campaign of Clark, who was at that time the Speaker of the House of Representatives in Washington DC, against contender Woodrow Wilson collapsed, and so did the apparent short term viability of the song. In addition, there were contentions from other camps concerning the true authorship of the song, which led to protracted court battles. Subsequent payments for the song were withheld by Witmark, causing John Stark to initiate his own lawsuit concerning the erstwhile Dawg. In the end, the Starks prevailed in a 1914 appellate court decision.

At the same time Dawg was becoming a popular stage tune in New York and other venues where performers were looking for some "hick" aspects to their act. The Dawg grew legs again, starting a second life, and publisher Stark soon received the contracted payment based the court decision.

Carrie was dragged along for the ride, but came out only slightly scathed as the acknowledged composer of the work, or adaptor in the case of the chorus. It soon prompted all kinds of hound dog paraphernalia in the stores as well, and gave wannabe hound dogs everywhere a temporary place on the stage. The piece was also picked up by the Second Missouri Infantry as their marching song, and at times has been proposed as a state song for Missouri (in 1912, and officially in 1949, plus other mentions of this possibility over the past century). Starting in the 1920s it was recorded frequently, and remains in circulation in country, bluegrass and old-time music circles. It became an old dawg learning new tricks.

|

Carrie got back on the horse, and in 1914 put out two more songs as Cal. One, Tango Tangle, was a pseudo-tango, a dance and music form that was very popular at the time, and the other was a waltz, usually a safe bet for light but solid sales. In 1917 Carrie as Cal turned out another fine fox-trot/blues, which would be perhaps her last known tune in print. Baby Blues was also released as a song with lyrics by Margie Brandon, very likely the wife of another Stark composer Clarence E. Brandon. These were put out on the Stark's subsidiary Syndicate Music Company, a label reserved for pieces that didn't quite meet the standards of pieces issued under his main logo. But John Stark, who had lost his wife a few years before, was now trying to champion a nearly dead genre in his last gasps of rag publication, and soon Carrie lost her best outlet to jazz and old age. As of the 1920 census she again was shown with no occupation, and William as W.P. was listed this time as a music printer, rather than a publisher.

While she did not give up piano playing during the remainder of her life, Carrie more or less faded from public view for a while, and lost her husband Will Stark in the 1940s. Then came the release of the book They All Played Ragtime in 1950, and the acknowledgement, clearly found in the notes taken for the book, of Carrie's role in They Gotta Quit Kickin' My Dawg Aroun', which helped make her somewhat of a local celebrity again. Studio head Walt Disney heard the connection between Carrie and the Dawg and wrote to her requesting a copy. She could not find any extras, but discovered that she did not have even one copy of the piece. Eventually one was located in the collection of the Missouri Historical Society and she "autographed it for posterity."

The 1950 census showed Carrie residing with her widowed daughter Ruth, now a real estate saleswoman, and Ruth’s two teenaged sons. Caroline Bruggeman Stark lived much of her final two decades with her daughter in Brentwood and Kirkwood, suburbs of St. Louis, occasionally venturing out to public ragtime events as pictured above. She finally passed on in 1972 at age 91, just as the huge revival of the very pieces and the musical genre that her father-in-law had championed was getting underway.

Webster Mil Oungst was born in Iowa in 1854. For the 1870 census he was listed as an apprentice printer in Grand Junction, Iowa, and in 1880, as a printer and editor in Harlan, Iowa. He founded the Harlan Hub newspaper that year, and was married on September 27, 1881 to Rebecca Bechtoll. Throughout the 1880s and into the early 1890s he was the part owner of a couple of other newspapers, including the Shelby County Republican. The 1900 census found Webb and his wife Rebecca in Pueblo, Colorado, as a printer, and in 1910, as expected, in St. Louis working for a printing company. It may have been his connection with the newspaper business that got him involved with the Clark campaign. Certainly as an editor he was experienced as a wordsmith, and had been exposed to a number of rural dialects in his travels. Oungst showed a clear comprehension of these in his clever phrasing and spellings in the lyrics of They Gotta Quit Kickin' My Dawg Aroun'.

As of 1920 Webb and his wife were back in Iowa, now residing in Waterloo, again working as a printer, but evidently nearing retirement. For the 1940 enumeration the couple was shown as living in Fort Smith, Arkansas, with their daughter Abbie, her husband Louis B. Barry, and their grandson Louis W.. Webb Oungst died in Fort Smith, on March 28, 1943, followed by Rebecca four and a half years later. But it would be over 60 years before Oungst would be more widely recognized as more than a footnote or a pseudonym associated with a politically charged theme song with its own fascinating history.

Thanks to Ragtime historian Sue Attalla, for much of the history and information on They Gotta Quit Kickin' My Dawg Aroun' and its association with Clark. Sue is also responsible for the verification of my independent research on Webb Oungst's identity and his role in the piece. Also thanks as always to Ragtime Women Historian Nora Hulse for some of the chronology of Carrie Stark's life. All additional information was researched directly by the author.