|

Edward Browne Claypoole (December 20, 1883 to January 16, 1952) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1899

Prancin' JimmyAin't No Coon Gwine to Keep Me Down [1] Make Haste, Mister N*****, Make Haste[1] Since Dis “Rag-Time” Done Come 'Round [1,2] 1900

Cake Walk Lindy1904

Hike to the Pike1905

Pansy Blossom [3]1906

My Prairie Wildflower Sioux [1]1908

After Office Hours [4,5]The Queen of Belle Paree [4,5] I Don't Want to Marry You [5] My Sahara Belle [6] 1909

Reuben: A Rural Reminiscence1910

My Guiding Star (When in Joy or inGladness) [7] Little Echo: Song from Theecho [7] 1912

Nuvida: Oriental Intermezzo1913

Alabama Jigger: Character RagImam [Markstern Guitar Folio only] 1914

Reuben Fox TrotIn Revolutionary Mexico [8] Why Don't You Get Yourself a Girl Like Me [8] Then He'd Put Another Record On [8,9] 1915

Ragging the Scale1916

American Jubilee: Patriotic RagSpooky Spooks: Fox Trot 1917

Echoes UniqueKirmanshah: Oriental Intermezzo 1918

Chicken Cackle: A Barnyard Concert1919

Movie Stuff: A Musical Scenario1920

Jazzapation - Fox-Trot |

1922

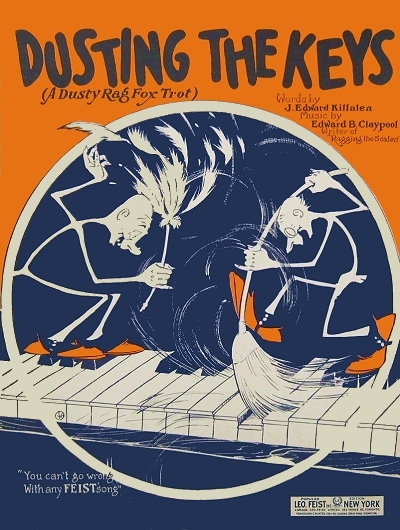

Dusting the KeysWaltzing Jim Changes Dusting the Keys (Song) [10] 1923

Skidding1924

Bouncing on the KeysGay Birds 1927

Shades of Blue1928

Rosette: CapriceLa Petite Demoiselle Gay Deceivers: Intermezzo Our Gang: Kid Komedy Karackteristik 1929

Oriental FantasyThe Song of the Baltimore Athletic Club [10] 1933

ZazaI Wonder [11] 1936

Two Notes [12]1939

Guess Who [13]1940

Slap-HappyTrying [13] 1941

Tapping on IvoryNight in Nassau 1949

Snow in the Moonlight1951

Lawn Party

1. w/Robert G. Claypoole

2. w/George D. Iverson, Jr. 3. w/Charles Bowen 4. w/Seymour Furth 5. w/Will Heelan 6. w/Harry Bache Smith 7. w/James R. Brewer 8. w/Leonard Weinberg 9. w/Elmer L. Greensfelder 10. w/Edward J. Killalea 11. w/Harry J. Matthews 12. w/Marty Symes 13. w/Roy Bergere |

Edward Claypoole was truly a court composer; literally. In spite of a pretty good legacy of great compositions, he spent his career working in the courts. Born in Baltimore to court clerk Captain James Yeardsley Claypoole and his wife Mary (Molly) H. Green, both Maryland natives, Eddie was the youngest of five children, including Robert Garland (3/31/1875), James Yeardsley, Jr. (6/4/1876), Genevieve W. (11/10/1879) and Martha Ann (10/31/1881). Captain Claypoole, who spent several years piloting boats at sea before the Civil War, was also involved in politics in Baltimore, part of his circle of friends in his position as a clerk in the Court of Common Pleas. Edward would spend virtually all of his life in Baltimore.

Little Eddie was drawn to the piano at an early age, and in his formative years his abilities were demonstrated by his proud mother as he was propped up on cushions picking out tunes. There was a brief foray with formal lessons that did not work out, so they were soon abandoned. As a result, Eddie was mostly self-taught, focusing on popular music forms, and without harmony or theory training unable to notate. His high school music teacher helped him out with the latter when Eddie decided he wanted to submit pieces for publication. Some of the earliest were written for school or community theater presentations. But instrumentals were soon to follow.

There is some question as to whether Edward was already contributing to ragtime music when he was but 15 years old. There are a couple of copyrights from 1899 attributed to the Claypoole Brothers. One song, Holding Hands, has been verified to have been composed by Robert G. Claypoole, in collaboration with George D. Iverson, Jr. But Iverson also had his name attached to Since Dis “Rag-Time” Done Come ‘Round along with the Claypoole Brothers, and given Edward’s talent, it is not unreasonable to surmise that he and Robert where the brothers in question. Two other less savory titles were produced by the brothers without Iverson, including There Ain’t No Coon Gwine to Keep Me Down, and the racially-charged Make Haste, Mister N*****, Make Haste. (Beyond this point, Edward’s output was much more palatable.) These were all published in New York City, so had the benefit of some circulation, and got Edward’s foot in the door, although he had to restart back at home.

The first of his solo works was Prancin' Jimmy when he was just 16, which did fairly well for Baltimore publisher Cohen and Hughes.  It also encouraged him to do more than just play in local venues, so he kept writing. As James had died in October 1895, the 1900 enumeration showed Eddie's mother as widowed, and Eddie was still in school. Curiously the enumerator caused some confusion by listing her name as Martin, and showing her as male, and a court clerk. But given confirmation of James' death and an apparent change on the record, this was a sloppy oversight as the other enumerated information matches.

It also encouraged him to do more than just play in local venues, so he kept writing. As James had died in October 1895, the 1900 enumeration showed Eddie's mother as widowed, and Eddie was still in school. Curiously the enumerator caused some confusion by listing her name as Martin, and showing her as male, and a court clerk. But given confirmation of James' death and an apparent change on the record, this was a sloppy oversight as the other enumerated information matches.

It also encouraged him to do more than just play in local venues, so he kept writing. As James had died in October 1895, the 1900 enumeration showed Eddie's mother as widowed, and Eddie was still in school. Curiously the enumerator caused some confusion by listing her name as Martin, and showing her as male, and a court clerk. But given confirmation of James' death and an apparent change on the record, this was a sloppy oversight as the other enumerated information matches.

It also encouraged him to do more than just play in local venues, so he kept writing. As James had died in October 1895, the 1900 enumeration showed Eddie's mother as widowed, and Eddie was still in school. Curiously the enumerator caused some confusion by listing her name as Martin, and showing her as male, and a court clerk. But given confirmation of James' death and an apparent change on the record, this was a sloppy oversight as the other enumerated information matches.One of Edward's big breaks came in 1903. Sort of. That was when he decided, despite some early musical successes, to get a real job. His older brothers Robert and James were also employed as clerks as their father had been, making it kind of a family affair. Whether older sisters Jessica and Martha followed is not clear. So, he applied to the Baltimore courts and got a job as an apprentice court clerk. They were very forgiving of his performance habits, however, and Edward was one of their best representatives in that regard.

Having a few pieces under his belt and a reputation as a good pianist, Claypoole found his way to the 1904 Lewis and Clark Exposition in St. Louis where he performed, and also had his own contribution to the large catalog of "Pike" pieces published, the Pike being the strip just outside of the fairgrounds where most of the ongoing entertainments were housed. Hike to the Pike did well at the fair, but so many pieces like this were soon forgotten. It was touted in the July 9, 1904, edition of The Music Trade Review as "a ready and rapid seller, and bands and orchestras in and around St. Louis and the fair are playing it right along."

In his new position as a court clerk in training Edward was able to turn out just a few pieces a year, if that, but they were usually accepted for publication. Two breaks came on Broadway as three of his songs were interpolated into two stage shows. The first, Nearly a Hero of 1908, including I Don't Want to Marry You and My Sahara Belle, ran several months for a total of 116 performances. However, the show received tepid reviews at best, and producer Lee Shubert suggested it might be renamed Nearly a Zero. Claypoole is credited with perhaps also having added lyrics only to a couple of the Seymour Furth songs.

The second production, The Echo of 1910, included My Guiding Star and ran for a shorter period of 53 performances, but it helped cement Claypoole's reputation as a solid composer. One other off-Broadway production of 1910, Theecho, yielded another two songs but no hits. But clearly by 1910 his footing was more solid in Baltimore. The census showed him with Adele "Addie" C. Spurrier, whom he had married on June 30, 1908, and with a daughter, Audrey C. Claypoole, born in late 1909. He was listed as a Law Court Clerk, but not as a musician.

One other off-Broadway production of 1910, Theecho, yielded another two songs but no hits. But clearly by 1910 his footing was more solid in Baltimore. The census showed him with Adele "Addie" C. Spurrier, whom he had married on June 30, 1908, and with a daughter, Audrey C. Claypoole, born in late 1909. He was listed as a Law Court Clerk, but not as a musician.

One other off-Broadway production of 1910, Theecho, yielded another two songs but no hits. But clearly by 1910 his footing was more solid in Baltimore. The census showed him with Adele "Addie" C. Spurrier, whom he had married on June 30, 1908, and with a daughter, Audrey C. Claypoole, born in late 1909. He was listed as a Law Court Clerk, but not as a musician.

One other off-Broadway production of 1910, Theecho, yielded another two songs but no hits. But clearly by 1910 his footing was more solid in Baltimore. The census showed him with Adele "Addie" C. Spurrier, whom he had married on June 30, 1908, and with a daughter, Audrey C. Claypoole, born in late 1909. He was listed as a Law Court Clerk, but not as a musician.Mildly diminutive at 5'4", Eddie was a local celebrity in Baltimore in the 1910s, and in demand for a number of musical functions. It was also one of his more productive writing periods. Alabama Jigger became a popular band hit, and his Reuben Fox Trot a decent seller. Then he tipped the scales of justice in his favor with - the scale. The simple concept of applying syncopation to a scale - a scale played in five different tonalities no less - earned Claypoole a permanent place in the ragtime hit parade.

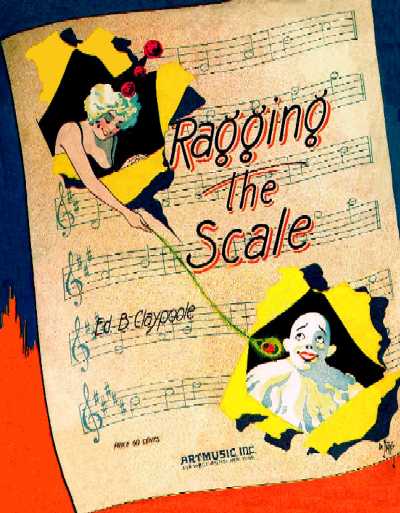

Appearing first in a beautiful but limited-edition clown cover (inexplicably replaced by a fairly generic notated cover), Ragging the Scale was a sensation for Eddie, as well as for Will Von Tilzer's Broadway Music Corporation, where it landed following its initial and more colorful printing issued by Von Tilzer's ArtMusic subsidiary. It sold well, was performed often around the country, and was one of the most cleverly simple pieces of the ragtime era. Within a year the piece had found its way to several different piano roll renditions. This sensation earned the erstwhile court clerk a total of $25.00, since he sold it outright rather than opt for royalties. Why take chances on a fad? But his tunes were still in demand. Ragging the Scale also made a comeback in a 1930s edition through ArtMusic. However, shortly after this Claypoole took a break from writing.

Meanwhile, Robert got busy with his pen again and contributed a few wartime tunes into the mix in 1918. The 1920 enumeration showed the Claypoole family still in Baltimore, with Edward listed as a Court Clerk at the Court House.

|

In the early 1920s Edward decided to test the waters again, and came up with the clever Dusting the Keys which actually included a little gimmick where the player was to literally dust the keys with a cloth on their index finger in the trio. With lyrics added in short order to create a song edition of the piece, it was yet another hit, but now completely in the novelty genre. Encouraged, he wrote four piano novelties that were all readily printed up by Mills Music, a leader in that genre during the 1920s. He also joined ASCAP in 1929.

While very few pieces followed his Mills novelties into print, Claypoole became a popular fixture on the radio in the late 1920s and into the 1940s. His daughter Audrey, shown still living in the family home in 1930 (when he had graduated to his ultimate position as Deputy Clerk) sang with him as well both on the radio and at live venues. Both the 1940 census and his 1942 draft card reinforce that he was still a court clerk, not a professional musician, something that may have given Addie some comfort.

The 1950 census showed Claypoole as still employed by the city as a court clerk, and Audrey, now divorced, as the secretary of a retail music company. Edward had retired from music by that time, and after a 45-year career, from the Baltimore City courts as well. One might imagine the sense of loss felt by the court when their finest musical representative left for retirement. A handful of pieces came out just around the time he left that job. Sadly, Edward's retirement, during which he penned only two more works, was a mere two years, as he died at age 68 in early 1952. But thankfully his many fine tunes have since come out of retirement to entertain us all. If it should please the court.

Some of the narrative of Claypoole's life was derived from the extraordinary efforts of Dave Jasen and Gene Jones in the book That American Rag published in 2000. It is a highly recommended source for a very different look at where ragtime came from and how it eventually reached the public. The rest was uncovered by the author in collective public records and articles from the ragtime era. The error in the 1900 census was pointed out to the author by researcher Barry Chapman who found the misalignment with the death of James five years prior.