Euday Louis Bowman (November 9, 1886 to May 26, 1949) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1914

12th Street Rag6th Street Rag 10th Street Rag Kansas City Blues Colorado Blues 1915

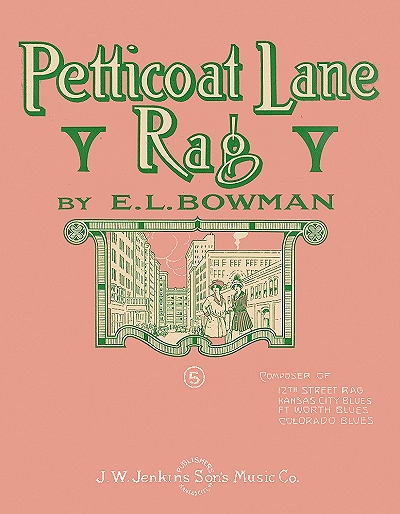

12th Street Rag (redux)Fort Worth Blues Petticoat Lane Tipperary Blues 1916

Rosary BluesShamrock Rag 1917

That's Teasing Them All, One and All11th Street Rag 1919

12th Street Rag Song [3]1921

Water Lily's DreamThen They Wonder Why a Boy Will Leave His Happy Home [1] 1922

Jolly Jazz Blues [1]1924

Jubilee's Ball [1] |

1925

Exercise No 2. 3. 1.C.C. Blues [1] 1926

Lie'in Papa [1]Chromatic Chords 1936

Texas Centennial Jubilee [1]1938

I Dreamed of Paradise [1]Hiding Your Love [1] She's the One for Me [1] Dream Island [1] 1940

Main Street Rag1943

Old Glory On Its Way [1]12th Street Rag Song [3] 1945

Spider on the Wall [1]19??

Forgotten Rose [2, 5]

1. Library of Congress Collection

2. University of North Texas 3. w/James S. Sumner 4. w/Andy Razaf 5. w/Edward Payne |

Known Discography Known Discography | |

|

1923

12th Street Rag [note that label statesit is Richard M. Jones, but it is more likely to be Bowman] 1924

12th Street Rag [Unreleased Pressing]1948

12th Street RagBaby is You Mad at Me? |

Matrix and Date

[Gennett 11493] 06/01/1923[Bowman A-11748 B] ??/??/1948 |

Often associated with Kansas City (at least in composition), Euday Bowman was actually a native of Texas, and his pieces fall under the category of "Texas Ragtime", a unique style all to itself. He was born in Tarrant County near the Fort Worth area to Kentucky native carpenter George A. Bowman and his Dutch immigrant wife Olivia Marguerite Graham Estee Lambin De Eske. Euday was the youngest of three siblings, including his sister Mary (5/1877) and brother Julius (9/1880). Two others had died in infancy. While his birth year has been traditionally cited as 1887, it is listed specifically as 1886 in the 1900 census and on his 1917 draft record, therefore 1886 will be assumed here as most correct. There have also been assertions that he was a light-skinned black. However, looking back into his lineage his mother is absolutely white, and his father is listed as such going back to the 1870s, so such speculation is false. Bowman was further listed as white in all census and draft records in which he appears.

There have also been assertions that he was a light-skinned black. However, looking back into his lineage his mother is absolutely white, and his father is listed as such going back to the 1870s, so such speculation is false. Bowman was further listed as white in all census and draft records in which he appears.

There have also been assertions that he was a light-skinned black. However, looking back into his lineage his mother is absolutely white, and his father is listed as such going back to the 1870s, so such speculation is false. Bowman was further listed as white in all census and draft records in which he appears.

There have also been assertions that he was a light-skinned black. However, looking back into his lineage his mother is absolutely white, and his father is listed as such going back to the 1870s, so such speculation is false. Bowman was further listed as white in all census and draft records in which he appears.For part of his childhood Euday and his siblings lived with their paternal grandfather, Gatewood Bowman, near Mansfield, Texas. Gatewood also reportedly visited Kansas City from time to time with Euday in tow. His parents were divorced in 1905 when he was in his late teens, and Olivia moved in with Mary and Euday. Given that both his mother Olivia and sister Mary were music teachers, Mary working for the Fort Worth school system, it is likely they were both largely responsible for Euday's earliest exposure to piano and composition. Mary is listed as a music teacher at 23 in the 1900 census.

Following a few attempts at writing in his teens and early twenties, Bowman struck out on his own as an itinerant pianist, playing largely in the prostitution districts of large towns and cities where the better bordellos were located. It has been sometimes reported that young Euday allegedly lost a leg while trying to hop a train during. However, this story is contradicted by his 1917 draft record which showed no infirmities to prevent him from being enlisted. (Research by Sarah Gjerstad suggests that this was a mix-up in identity, since Bowman's older cousin Almer Campbell did lose the use of his leg while hopping on a yard engine in 1898.) In 1910 Bowman was still living in Fort Worth, at least part of the time, with Olivia (now showing as a widow) and older sister Mary, both working as music teachers. Euday was listed as a teamster.

After spending some time working and playing piano in the districts in both Fort Worth and Kansas City, Bowman composed the 12th Street Rag. He claimed it was as early as 1905, but this is hard to confirm. As noted in his obituary in 1949:

It was in his teens that he wrote the first part of the three-note tune which became nationally famous. When a friend opened a pawn shop, Bowman told him waggishly that if a three-ball shop could succeed, he could write a three-note song that would survive

It was melodically simple due to its secondary rag three over four pattern, which made it easy to play by ear and to improvise on, creating a durable hit once it was published many years later. However, when performed directly from the sheet music using the octaves in the original score, it becomes a bit more challenging. In fact, the first self-publication of this rag, submitted for copyright on January 2, 1915, was deemed nearly impossible to play, particularly the introduction and third strain. It was revamped for a second edition of around 500 to 1000 copies, signified by a hand-stamped copyright.

However, when performed directly from the sheet music using the octaves in the original score, it becomes a bit more challenging. In fact, the first self-publication of this rag, submitted for copyright on January 2, 1915, was deemed nearly impossible to play, particularly the introduction and third strain. It was revamped for a second edition of around 500 to 1000 copies, signified by a hand-stamped copyright.

However, when performed directly from the sheet music using the octaves in the original score, it becomes a bit more challenging. In fact, the first self-publication of this rag, submitted for copyright on January 2, 1915, was deemed nearly impossible to play, particularly the introduction and third strain. It was revamped for a second edition of around 500 to 1000 copies, signified by a hand-stamped copyright.

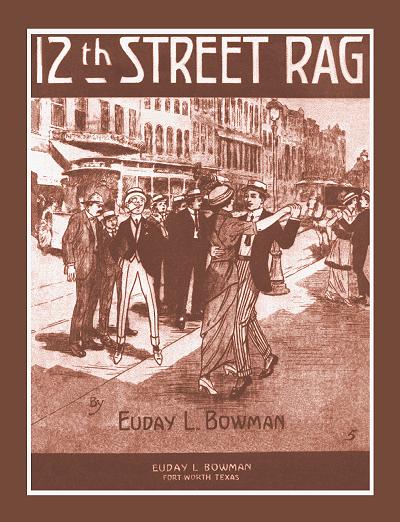

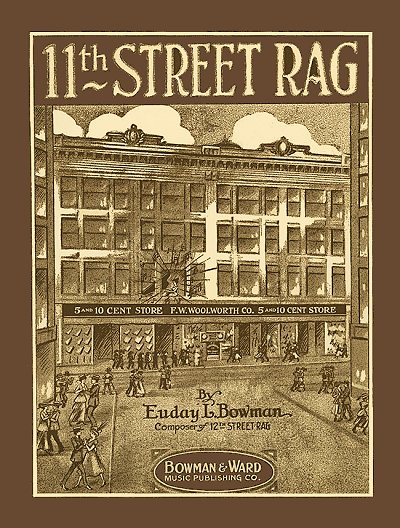

However, when performed directly from the sheet music using the octaves in the original score, it becomes a bit more challenging. In fact, the first self-publication of this rag, submitted for copyright on January 2, 1915, was deemed nearly impossible to play, particularly the introduction and third strain. It was revamped for a second edition of around 500 to 1000 copies, signified by a hand-stamped copyright.After limited success in trying to market the piece by himself for four years, and looking to cover his costs, Bowman sold the rag to the Jenkins Publishing firm in Kansas City for a mere $300 in 1919. They marketed it well and helped convert the rag into the popular version that is still available into the 21st century. Whether 12th Street Rag was named after 12th Street in Kansas City, or the same in either Dallas or Fort Worth, all of which had a 12th Street in the entertainment and red-light district, is a question of where he was when he wrote it or where he was thinking of, and this is not entirely verified. However, the first of three sets of lyrics added at a later date start out "Down in Kansas City...", likely a choice of the rag's Kansas City publisher or the lyricist he chose. A further clue would be on the covers of both the 11th Street Rag and 12th Street Rag, which have drawings of downtown Kansas City, including the large F.W. Woolworth store, and his piece Petticoat Lane, which is clearly related to Kansas City.

Based on his post-sale success with 12th Street Rag Bowman wrote rags for Sixth Street, Tenth Street and Petticoat Lane, and had a minor success with the 11th Street Rag. Most of his compositions from this point were blues that were based in his Texas musical heritage, but also contained elements of good ragtime. They were initially published by a house he set up with a partner, Bowman and Ward. Unfortunately, once he sold 12th Street Rag and later some of the other Bowman and Ward scores to Jenkins, such as Kansas City Blues, for a relatively paltry sum, he did not see any more revenue from any of them despite the enormous national hit status of his most popular piece. For them it was just business, but it haunted Bowman for many years as he struggled to make a living. On his 1918 draft record he listed himself as a musician, but also as "not employed." Bowman was still living in Fort Worth in 1920 with his mother and sister, working as an equipment operator of some kind.

Most of his compositions from this point were blues that were based in his Texas musical heritage, but also contained elements of good ragtime. They were initially published by a house he set up with a partner, Bowman and Ward. Unfortunately, once he sold 12th Street Rag and later some of the other Bowman and Ward scores to Jenkins, such as Kansas City Blues, for a relatively paltry sum, he did not see any more revenue from any of them despite the enormous national hit status of his most popular piece. For them it was just business, but it haunted Bowman for many years as he struggled to make a living. On his 1918 draft record he listed himself as a musician, but also as "not employed." Bowman was still living in Fort Worth in 1920 with his mother and sister, working as an equipment operator of some kind.

Most of his compositions from this point were blues that were based in his Texas musical heritage, but also contained elements of good ragtime. They were initially published by a house he set up with a partner, Bowman and Ward. Unfortunately, once he sold 12th Street Rag and later some of the other Bowman and Ward scores to Jenkins, such as Kansas City Blues, for a relatively paltry sum, he did not see any more revenue from any of them despite the enormous national hit status of his most popular piece. For them it was just business, but it haunted Bowman for many years as he struggled to make a living. On his 1918 draft record he listed himself as a musician, but also as "not employed." Bowman was still living in Fort Worth in 1920 with his mother and sister, working as an equipment operator of some kind.

Most of his compositions from this point were blues that were based in his Texas musical heritage, but also contained elements of good ragtime. They were initially published by a house he set up with a partner, Bowman and Ward. Unfortunately, once he sold 12th Street Rag and later some of the other Bowman and Ward scores to Jenkins, such as Kansas City Blues, for a relatively paltry sum, he did not see any more revenue from any of them despite the enormous national hit status of his most popular piece. For them it was just business, but it haunted Bowman for many years as he struggled to make a living. On his 1918 draft record he listed himself as a musician, but also as "not employed." Bowman was still living in Fort Worth in 1920 with his mother and sister, working as an equipment operator of some kind.Euday again tried to strike out on his own, marrying Miss Geneva Morris on October 19, 1920, in Erath, Texas. However, the union was problematic, and Geneva abandoned their home by mid-1921. Their divorce was finalized in 1926. During the 1920s, when radio broadcasting was quickly becoming established around the world, Euday and Mary seemed to be good candidates as home town musicians to contribute to one of the new stations on the air in Fort Worth. One of those appearances was reviewed in the Fort Worth Star Telegram on May 12, 1924:

RAG COMPOSER PERFORMS FOR WBAP

Euday L. Bowman, pianist and composer of the famous “12th Street Rag” and other songs, entertained the radio listeners with 40 minutes of first class piano music Sunday afternoon beginning at 5 o’clock.

He was assisted by Grace Shields, 13 year-old pupil of Mary M. Bowman, the young artist scoring a real hit in her several selections. Among her numbers were “Valse” by Durand, “The Joyous Peasant” by Schuman and “Polonaise Militaire” by Chopin.

Miss Bowman offered some beautiful selections, among them being “Remembrance” and “Pizzicati,” while Euday Bowman won favor with Radioland in three offerings, “Water Lily’s Dream,” “Fade Away Waltz,” and “Medley of Selections,” all of his own composition.

In 1930 he was still living with his sister, their mother having died in 1922, but Euday was now shown as a pianist and jazz teacher, having gained some fame from his most famous work. During the 1920s and 1930s Bowman also submitted a number of other pieces to the Library of Congress, likely wary of repeating his 12th Street Rag experience, but they were not published, remaining in manuscript form. (Some of these works are now available at the Library of Congress web site for viewing.) The 1940 enumeration taken in Fort Worth showed him as a music teacher with his own studio, while Mary had evidently retired from piano instruction.

During the 1920s and 1930s Bowman also submitted a number of other pieces to the Library of Congress, likely wary of repeating his 12th Street Rag experience, but they were not published, remaining in manuscript form. (Some of these works are now available at the Library of Congress web site for viewing.) The 1940 enumeration taken in Fort Worth showed him as a music teacher with his own studio, while Mary had evidently retired from piano instruction.

During the 1920s and 1930s Bowman also submitted a number of other pieces to the Library of Congress, likely wary of repeating his 12th Street Rag experience, but they were not published, remaining in manuscript form. (Some of these works are now available at the Library of Congress web site for viewing.) The 1940 enumeration taken in Fort Worth showed him as a music teacher with his own studio, while Mary had evidently retired from piano instruction.

During the 1920s and 1930s Bowman also submitted a number of other pieces to the Library of Congress, likely wary of repeating his 12th Street Rag experience, but they were not published, remaining in manuscript form. (Some of these works are now available at the Library of Congress web site for viewing.) The 1940 enumeration taken in Fort Worth showed him as a music teacher with his own studio, while Mary had evidently retired from piano instruction.Finally in 1937, even before the original copyright renewal was available following the initial 26-year period, Euday was able to get the rights back to his beloved and now quite famous 12th Street Rag. However, he made little return from it during the war years and even soon after, despite reprints and promotion of the piece. It had been recorded by many prominent musicians over the past two decades, including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, arranger and bandleader Fletcher Henderson, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, and many New Orleans traditional jazz musicians. Bowman eventually reassigned the copyright to publisher Shapiro-Bernstein. He also joined ASCAP in 1946 to ensure even more protection for and revenue from his popular rag. He moved back in with his sister soon after that, and there are reports that he was engaged collecting and selling junk, although they are difficult to substantiate.

In early 1948, big band leader Pee Wee Hunt inadvertently recorded Bowman's most famous opus during a radio show transcription session in Nashville for Capitol Records, when the engineer informed him there was still a little space left on the disc. The arrangement was silly in places with a doo-wacka-doo chorus by the trumpets, and the questionably pitched piano used for a solo passage was at least a quarter step flat. Not intended for airplay, the recording was nonetheless broadcast by stations all over the country, ironically during a musician's strike when studio recordings other than for the radio were being boycotted. The public demand for the track was nearly immediate, and caught Capitol Records by surprise. They soon released it on a 78 RPM single, and as a result the 12th Street Rag once again became a nostalgic hit, finding its way to number one on the pop charts for six weeks from August into October, then another two weeks in late October. It became the overall top selling record of 1948.

Not intended for airplay, the recording was nonetheless broadcast by stations all over the country, ironically during a musician's strike when studio recordings other than for the radio were being boycotted. The public demand for the track was nearly immediate, and caught Capitol Records by surprise. They soon released it on a 78 RPM single, and as a result the 12th Street Rag once again became a nostalgic hit, finding its way to number one on the pop charts for six weeks from August into October, then another two weeks in late October. It became the overall top selling record of 1948.

Not intended for airplay, the recording was nonetheless broadcast by stations all over the country, ironically during a musician's strike when studio recordings other than for the radio were being boycotted. The public demand for the track was nearly immediate, and caught Capitol Records by surprise. They soon released it on a 78 RPM single, and as a result the 12th Street Rag once again became a nostalgic hit, finding its way to number one on the pop charts for six weeks from August into October, then another two weeks in late October. It became the overall top selling record of 1948.

Not intended for airplay, the recording was nonetheless broadcast by stations all over the country, ironically during a musician's strike when studio recordings other than for the radio were being boycotted. The public demand for the track was nearly immediate, and caught Capitol Records by surprise. They soon released it on a 78 RPM single, and as a result the 12th Street Rag once again became a nostalgic hit, finding its way to number one on the pop charts for six weeks from August into October, then another two weeks in late October. It became the overall top selling record of 1948.Bowman reportedly bought a very nice car with his first royalty check in early 1949, but it was the only such check for that piece he would ever see. He tried to capitalize on the success of Hunt's recording by promoting himself and his other works, including making his own record of the famous piece on a private label, allegedly recorded on the same piano on which he composed it.

Possibly newly confident that he could afford a better lifestyle, Euday married again, this time to Ruth Emma Thompson on February 6, 1949. However, he had a change of heart within a month, filing for divorce in mid-March on grounds of cruelty inflicted by his wife. To add to his troubles, Euday's health had deteriorated, and the physical and financial strain proved to be too much for him. His good fortune was offset by over $2,000 in medical bills. Still, he attempted a trip to New York City to publicize his authorship and recent recording of the rag. Euday Bowman succumbed there from pneumonia in a New York hospital. at age 61 or 62 just as his star was rising again.

Still, he attempted a trip to New York City to publicize his authorship and recent recording of the rag. Euday Bowman succumbed there from pneumonia in a New York hospital. at age 61 or 62 just as his star was rising again.

Still, he attempted a trip to New York City to publicize his authorship and recent recording of the rag. Euday Bowman succumbed there from pneumonia in a New York hospital. at age 61 or 62 just as his star was rising again.

Still, he attempted a trip to New York City to publicize his authorship and recent recording of the rag. Euday Bowman succumbed there from pneumonia in a New York hospital. at age 61 or 62 just as his star was rising again.Mary Bowman inherited the rights to 12th Street Rag and Euday's other copyrights, supposedly assuring her comfort and to possibly acknowledge her help in either writing or at least notating some of them so many years before. However, his iconic piece would not die, and would even be embroiled in legal controversy due to its new-found popularity. Shapiro-Bernstein believed that as the copyright owner of Bowman's instrumental they also allegedly owned by proxy the song version by Sumner and all versions that used the famous melody. A 1949 lawsuit was filed by them against publisher Jerry Vogel as he had acquired the rights to Sumner's 1919 version of the song with lyrics in 1947, and started distributing it. Vogel countersued saying that Shapiro-Bernstein owed him money based on the Jenkins' acquisition of the tune since Bowman's copyright renewal did not include the lyrics. The first decision in 1950 found that it was a "composite work" and that Sumner's lyrics did not constitute a right to the instrumental version.

In 1954 an appeals court found that since Jenkins' intent was for the music and lyrics to be performed together, they were part of a cohesive single "joint work." This allowed Vogel to collect 50% of the profits from Shapiro-Bernstein for the instrumental version sales with the Sumner lyric. He then went after compensation based on sales of no less than 22 other versions of the work. The final verdict on what was or was not copyrightable in terms of changes to an original piece came in 1957, argued for Shapiro-Bernstein by music lawyer Lee Eastman (father of Linda Eastman-McCartney) and esteemed music critic Deems Taylor. Even though it was settled out of court the entire affair was considered to be precedent-setting case by that time, and resulted in revisions to United States copyright law. Vogel gave up claim to his 50% of the royalties from 1941 to 1957 on the non-Sumner versions, but did manage to get 33% of all subsequent royalties and joint publication credit for all 12th Street Rag variations. A similar suit he had against ASCAP was also settled out of court on the same terms.

The lasting impact of this simple Texas musician's most famous work remains with us today. Even after Bowman died and while the song was tied up in a decade-long contentious court battle, artists as diverse as the Firehouse Five Plus Two and Liberace were keeping his memory alive through that one ubiquitous tune. It is also available on an endless array of CDs, and even DVDs of old Vitaphone shorts and Disney cartoons in which it was liberally featured. Almost every traditional jazz or ragtime festival around the world features a performance of the rag at some point, often as a finale with a mass of musicians gathered around any piano on the stage making ebullient contributions to the fray. All this from a piece which had been born and raised in the brothels of Texas.

Thanks to Adam Swanson who has a rare copy of Bowman's 1948 record and gave the info on it, as well as relaying information from the late Mike Montgomery on the probable 1923 side for Gennett. Also, family researcher Sarah Gjerstad for other points of information on Bowman.