Artie Matthews (November 15, 1888 to October 25, 1958) | |

Compositions Compositions |

Arrangements |

|

1908

Give Me, Dear, Just One More Chance[w/Ford Hayes] 1912

Twilight Dreams [1]Wise Old Moon [1] Everybody Makes Love to Someone [w/P. Franzi] Waiting [w/Emma Ettienne] 1913

Lucky Dan, My Gamblin' Man [2]When I'm Gone [2] The Princess Prance [2] Old Oak Tree by the Wayside [w/T. Hilbren Schaefer] Pastime Rag #1 Pastime Rag #2 1915

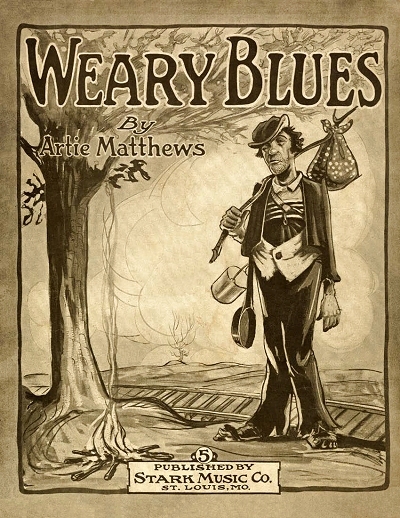

Weary BluesWeary Blues (Song) [3] 1916

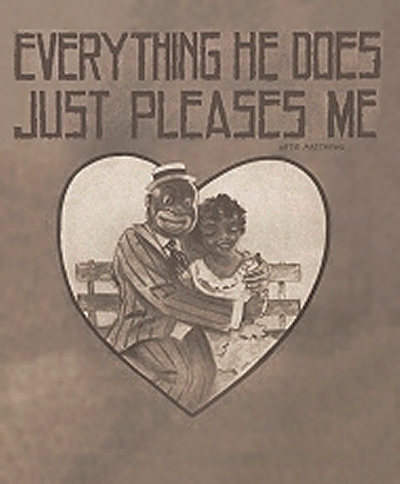

Pastime Rag #3Everything He Does Just Pleases Me 1918

Pastime Rag #51920

Pastime Rag #41922

Ethiopia: Cantatac.1930

Who Am I?c.1940

A Caress [w/Maxie Earhart Clark]1943

If You Would Know the Bible: Hymn.

1. w/H. Inman

2. w/Charles A. Hunter 3. w/Mort Greene & George Cates |

1911

Dat Afro American Rag[Jesse Duke & David L. Moore] My Senorita Marie [Jesse Duke & David L. Moore] In the Moonlight by the Pyramids [Jesse Duke & David L. Moore] 1912

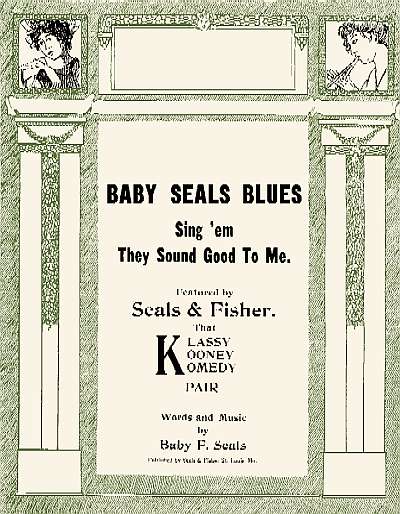

Baby Seals Blues[Baby F. Seals] Well, If I Do, Don't You Let It Get Out [Baby F. Seals] They Gotta Quit Kickin' My Dawg Aroun' [Carrie Stark & Webb M. Oungst] 1913

Junk Man Rag[Charles Luckeyth Roberts] 1914

Lily Rag[Charles Thompson] Cataract Rag [Robert Hampton] My Tango Maid [Clarence E. Brandon] 1915

Agitation Rag[Robert Hampton] Jinx Rag [Lucian Porter Gibson] 1916

Cactus Rag[Lucian Porter Gibson] 1921

That Original Jazz Band of Mine[Leonard Jean Kahn] Say That I May Come Back to You [Leonard Jean Kahn] If You Must Be Caught [W.P. Dabney] |

Artie Matthews was born to Samuel Matthews and Mary "Mattie" Stratton in Braidwood, Illinois, just a bit southwest of Chicago and southeast of Joliet. Samuel was a coal mine shaft specialist, and when Artie was very young the family moved to Springfield, Illinois to facilitate his work with the Black Diamond coal shaft. Most of Artie's youth was spent in Springfield. The family was shown residing in Springfield in the 1894 directory living at 903 S. 12th Street. In the 1896 city directory, Mary Matthews was shown to be the widow of Samuel, who had died in 1895, likely as a result of his hazardous work. She and her children were living at 1417 E. Adams in Springfield. Mary Matthews (as Matthues) is also shown in Springfield in the 1900 census working as a laundress, and widowed, living at 921 S. 14th Street, just seven blocks south of the 1896 address. She had a boy with the exact birth month and year of Artie, but listed as Chalmers. There are no other close matches in Illinois, even under Arthur, Art or Artie. Enumerator errors have crept in quite often, as may be the case here. Many ragtime composers adopted their middle names, or dropped them in some cases, so the name of Artie Chalmers Matthews in his youth bears some possibility. The odds are very good that this was Artie, which means he had an older sister, Addie or Addia, born in 1885. While none of this has been absolutely confirmed, by eliminating the other handful of possibilities it becomes highly plausible.

Artie's initial musical training came from his mother. During the latter part of his teens he played in some of the bars and other public venues in Springfield. One of his first attempts to play in a large public venue was at the 1904 Lewis and Clark Exposition in St. Louis. However, the considerable competition presented by many forceful pianists there caused him to demur from this opportunity. Still, he wanted to perform ragtime well, and spent the next couple of years learning from two local ragtime pianists, Banty Morgan, a dope addict, and Art Dunningham. With their help and his own talent, he got positions playing everywhere from street corners to Springfield drinking establishments and bordellos.

When he was nearly 18-years-old, Artie moved south to St. Louis during the height of the ragtime era in 1907, finding the environment to be a much different place now that the Exposition was just a memory and many pianists had migrated to Chicago. There was less aggressive competition and more camaraderie among the pianists there. He was virtually immediately employed by famed composer and player Tom Turpin, who owned both the Rosebud Cafe and the Booker T. Washington Theater. It was here that Artie was able to hone his compositional and arranging skills, supplemented by formal training at the Keeton School of Music over a period of nearly five years. In 1908 he wrote and published his earliest known surviving piece, Give Me, Dear, Just One More Chance one of the only songs he also wrote lyrics for. Artie appeared in the 1910 census in St. Louis boarding at 7612 Pine Street, and was listed as a band musician.

While living in St. Louis Matthews made occasional trips to Chicago to listen to other pianists. It was there that he heard Tony Jackson several times. He also encountered Jelly Roll Morton in 1911 in St. Louis, although he may have heard Morton a bit earlier in Chicago. Of the two, he regarded Morton as the better player. In turn, Morton regarded Matthews as one of the finest that he had heard. There may be some credence to the thought that Morton acquainted Artie with the "Latin tinge" style that showed up in two of his later Pastime Rags. Artie mentioned Clarence Jones and Ed Hardin as skilled players ot that time as well. By 1911 Matthews was quite musically literate, able to sight read virtually anything and notate as well.

There may be some credence to the thought that Morton acquainted Artie with the "Latin tinge" style that showed up in two of his later Pastime Rags. Artie mentioned Clarence Jones and Ed Hardin as skilled players ot that time as well. By 1911 Matthews was quite musically literate, able to sight read virtually anything and notate as well.

There may be some credence to the thought that Morton acquainted Artie with the "Latin tinge" style that showed up in two of his later Pastime Rags. Artie mentioned Clarence Jones and Ed Hardin as skilled players ot that time as well. By 1911 Matthews was quite musically literate, able to sight read virtually anything and notate as well.

There may be some credence to the thought that Morton acquainted Artie with the "Latin tinge" style that showed up in two of his later Pastime Rags. Artie mentioned Clarence Jones and Ed Hardin as skilled players ot that time as well. By 1911 Matthews was quite musically literate, able to sight read virtually anything and notate as well.In the summer of 1912, Matthews became one of the earliest composers to arrange, notate and publish a true vocal blues song with "blues" in the title, the Baby Seals Blues, composed by highly popular Southern pianist H. Franklin "Baby" F. Seals as part of his vaudeville act with Miss Floyd "Baby" Fisher. This publication beat out W.C. Handy's Memphis Blues (originally Mister Crump) by just a few weeks, and was widely performed in black vaudeville from 1912 to 1914. Artie also worked out Well, If I Do, Don't You Let It Get Out for the team that same year.

During a later visit to Cincinnati Matthews met up and coming Harlem pianist Charles Luckeyth Roberts, and did the first known arrangement of his Junk Man Rag, a more formal sounding one than the more commonly heard Will Tyers arrangement. Back in St. Louis, Turpin put Artie to work for a season at his Booker T. Washington Theater, and Matthews was also engaged at Barrett's Theatorium and the Princess Roadhouse, composing works specifically for revues and shows at each venue. Sadly, many of these were commonly considered disposable properties in the theater at that time, and only titles exist for most of them now. Three of them did get published by the Princess management in 1913, following three songs Matthews had published on his own in 1912.

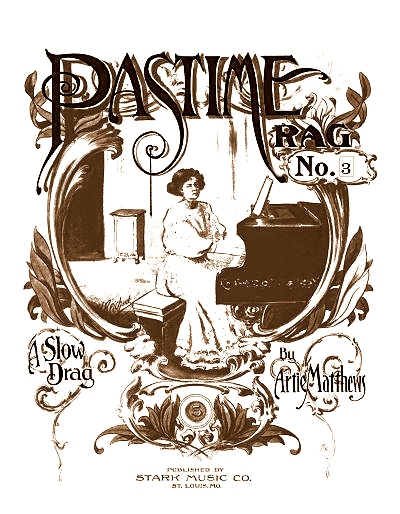

Word of Artie's talents spread and it eventually made its way to pioneer ragtime publisher John Stark or one of his children. Stark hired him as a principal arranger for his firm, and he helped create numerous classic rags from sketches by their original composers. The publisher reportedly then offered Matthews $50 outright for each rag he composed. Artie eventually turned in five masterpieces, the Pastime Rags, all believed to have been written from around 1912 to 1913. There were likely more rags, but these are the only five that exist. All had very unique elements that set them apart from other rags of the time, including creative stop time sections, tone clusters, walking bass lines, and advanced Latin rhythm integration. In particular, Pastime Rag #3 is unique among St. Louis rags for its habanera opening strain and dramatic eight bar second section, plus a silent four beat break in the trio. Pastime Rag #4 uses dissonance to great effect with moving tone clusters in the opening. Pastime #5 was a very powerful combination of tango and rag. The warning for each of these rags, "Don't fake", was likely added by Matthews as they don't appear in other Stark publications. But rather than an insistence that the performer play it exactly as written, it seems more like a simple request that the user learn the piece correctly before making it their own.

Artie eventually turned in five masterpieces, the Pastime Rags, all believed to have been written from around 1912 to 1913. There were likely more rags, but these are the only five that exist. All had very unique elements that set them apart from other rags of the time, including creative stop time sections, tone clusters, walking bass lines, and advanced Latin rhythm integration. In particular, Pastime Rag #3 is unique among St. Louis rags for its habanera opening strain and dramatic eight bar second section, plus a silent four beat break in the trio. Pastime Rag #4 uses dissonance to great effect with moving tone clusters in the opening. Pastime #5 was a very powerful combination of tango and rag. The warning for each of these rags, "Don't fake", was likely added by Matthews as they don't appear in other Stark publications. But rather than an insistence that the performer play it exactly as written, it seems more like a simple request that the user learn the piece correctly before making it their own.

Artie eventually turned in five masterpieces, the Pastime Rags, all believed to have been written from around 1912 to 1913. There were likely more rags, but these are the only five that exist. All had very unique elements that set them apart from other rags of the time, including creative stop time sections, tone clusters, walking bass lines, and advanced Latin rhythm integration. In particular, Pastime Rag #3 is unique among St. Louis rags for its habanera opening strain and dramatic eight bar second section, plus a silent four beat break in the trio. Pastime Rag #4 uses dissonance to great effect with moving tone clusters in the opening. Pastime #5 was a very powerful combination of tango and rag. The warning for each of these rags, "Don't fake", was likely added by Matthews as they don't appear in other Stark publications. But rather than an insistence that the performer play it exactly as written, it seems more like a simple request that the user learn the piece correctly before making it their own.

Artie eventually turned in five masterpieces, the Pastime Rags, all believed to have been written from around 1912 to 1913. There were likely more rags, but these are the only five that exist. All had very unique elements that set them apart from other rags of the time, including creative stop time sections, tone clusters, walking bass lines, and advanced Latin rhythm integration. In particular, Pastime Rag #3 is unique among St. Louis rags for its habanera opening strain and dramatic eight bar second section, plus a silent four beat break in the trio. Pastime Rag #4 uses dissonance to great effect with moving tone clusters in the opening. Pastime #5 was a very powerful combination of tango and rag. The warning for each of these rags, "Don't fake", was likely added by Matthews as they don't appear in other Stark publications. But rather than an insistence that the performer play it exactly as written, it seems more like a simple request that the user learn the piece correctly before making it their own.Several of the elements found in the Pastime Rags are also obviously present in the arrangements he did of other composer's works, especially those for Robert Hampton and Lucian Porter Gibson. Hampton had virtually no notation skills but a dynamic playing style that Matthews attempted to capture in his virtuoso arrangement of Cataract Rag. He also managed to turn Gibson's only known rags into alternate Pastime Rags with similar chord progressions and left hand rhythms. In 1915, Stark offered another $50 for any composer who could write a rag to compete with Handy's instantly popular St. Louis Blues. Matthews came through with the Weary Blues, which was so successful that Stark gave him $27 extra just to buy a new suit. This was a very impressive commendation for that time. Weary Blues was well covered and kept in standard jazz repertoire over the next couple of decades, forecasting Boogie Woogie among other styles. He brought out one more song with a different publisher in 1916, Everything He Does Just Pleases Me, then all but abandoned ragtime and popular music.

In late 1915 Matthews left St. Louis for Chicago where he spent some time peripherally in the music scene, also playing organ for the Berea Presbyterian Church. It was here he became reacquainted with classical music, particularly Bach and other baroque composers who had created hymn tunes. This further codified his desire to separate himself and his music from the environment in which black ragtime had traditionally been composed and performed in. About a year later Artie was called to come to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he would spend much of the rest of his life. Artie is listed on his 1917 draft card as a "choirmaster" at an Episcopal church, which was St. Andrews Episcopal Church, the organization that recruited him as their choral leader and organist as well. To improve his skills he received training in organ and theory from Professor W. S. Sterling of the Metropolitan College of Music of Cincinnati, earning a degree in 1918. Further studies were done with Frank Van der Stucken, conductor of the Cincinnati Symphone Orchestra, where he became well-versed in choral conducting, something he would excel at throughout his career at many musical presentations in Cincinnati. Around that time Artie met, then married fellow musician Anna Mazy Howard on July 4, 1918. The couple was shown living at 811 West Eighth Street in the 1920 census, both listed as musicians and teachers.

This further codified his desire to separate himself and his music from the environment in which black ragtime had traditionally been composed and performed in. About a year later Artie was called to come to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he would spend much of the rest of his life. Artie is listed on his 1917 draft card as a "choirmaster" at an Episcopal church, which was St. Andrews Episcopal Church, the organization that recruited him as their choral leader and organist as well. To improve his skills he received training in organ and theory from Professor W. S. Sterling of the Metropolitan College of Music of Cincinnati, earning a degree in 1918. Further studies were done with Frank Van der Stucken, conductor of the Cincinnati Symphone Orchestra, where he became well-versed in choral conducting, something he would excel at throughout his career at many musical presentations in Cincinnati. Around that time Artie met, then married fellow musician Anna Mazy Howard on July 4, 1918. The couple was shown living at 811 West Eighth Street in the 1920 census, both listed as musicians and teachers.

This further codified his desire to separate himself and his music from the environment in which black ragtime had traditionally been composed and performed in. About a year later Artie was called to come to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he would spend much of the rest of his life. Artie is listed on his 1917 draft card as a "choirmaster" at an Episcopal church, which was St. Andrews Episcopal Church, the organization that recruited him as their choral leader and organist as well. To improve his skills he received training in organ and theory from Professor W. S. Sterling of the Metropolitan College of Music of Cincinnati, earning a degree in 1918. Further studies were done with Frank Van der Stucken, conductor of the Cincinnati Symphone Orchestra, where he became well-versed in choral conducting, something he would excel at throughout his career at many musical presentations in Cincinnati. Around that time Artie met, then married fellow musician Anna Mazy Howard on July 4, 1918. The couple was shown living at 811 West Eighth Street in the 1920 census, both listed as musicians and teachers.

This further codified his desire to separate himself and his music from the environment in which black ragtime had traditionally been composed and performed in. About a year later Artie was called to come to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he would spend much of the rest of his life. Artie is listed on his 1917 draft card as a "choirmaster" at an Episcopal church, which was St. Andrews Episcopal Church, the organization that recruited him as their choral leader and organist as well. To improve his skills he received training in organ and theory from Professor W. S. Sterling of the Metropolitan College of Music of Cincinnati, earning a degree in 1918. Further studies were done with Frank Van der Stucken, conductor of the Cincinnati Symphone Orchestra, where he became well-versed in choral conducting, something he would excel at throughout his career at many musical presentations in Cincinnati. Around that time Artie met, then married fellow musician Anna Mazy Howard on July 4, 1918. The couple was shown living at 811 West Eighth Street in the 1920 census, both listed as musicians and teachers.In an effort to offer the African American population of Cincinnati and neighboring Covington, Kentucky opportunities to advance where few had previously existed, the couple opened the Cosmopolitan School of Music in 1921. This became the first conservatory of its kind in the country, perhaps the world, being owned by African Americans yet focusing on all forms of music, encouraging young black performers to embrace more than just ragtime and blues. It became an admirable example in Cincinnati and endured through the Great Depression of the 1930s. Many details of its history were published in the Cincinnati Post on April 6, 1943. Please note that a couple of passages reflect racial misperceptions of that time, and are included here for historical context only. Also note that his name is incorrectly spelled Mathews consistently throughout the article, even though on known documents he always signed as Matthews.

Among the splendid achievements of Negro citizens in Cincinnati, none is more outstanding than that of Artie Mathews, founder and director of the Cosmopolitan School of Music, 823 W. Ninth Street.

A Conservatory of Music for Negroes had been a long cherished hope among Negro groups, also among white groups interested in Negro welfare and who recognized the possibilities for the development of the latent musical talent in the colored race.

The old adage, "God helps those who help themselves," is most truly applicable to Artie Mathews…

Ever prompted by the vision of a recognized music school for the people of his race, Mr. Mathews set out in dead earnest to earn the money for its achievement. He started a studio in a small room on Eighth street. He served as choral conductor for the Public Recreation Commission under DeHart Hubbard and Harry Glore.

He established himself officially as a pianist director of cabaret and theater orchestras. With the help of his wife, Anna Howard Mathews, also a talented teacher of music, he was, after five years of strenuous work and earnest saving, able to claim a bank savings account of $1500.

With the sum for the initial payment he ventured in 1921 to purchase a building for the establishment of the proposed school. For $7000 he succeeded in buying the fine old resident on Ninth street, which now houses his institution. It was a courageous undertaking for Mr. Mathews. The road was not easy. Today [1943] he claims for his school the following enviable financial record:

A 14-room building with automatic gas-fired furnace. Adequate furnishings. Four grand pianos, three upright pianos, one combination radio and Victrola, and a library of more than 500 volumes, free of all indebtedness.

The Race Relations' Committee of the Woman's City Club has always felt a keen interest in the Cosmopolitan School of Music... In 1934, the committee won the unbounded and lasting gratitude of Mr. Mathews [by securing] a conference with [the Dean of] the Teacher's College at the University of Cincinnati, which resulted in the Cosmopolitan School of Music being placed on the accredited list of music schools in Cincinnati.

Artie spent most of the rest of his life offering quality music education to minorities, many which went on well prepared for a career in music. He also worked with many Cincinnati churches as a choir director and organist, and with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra as an arranger (the latter according to his son, although no confirmation has been located). He continued to compose, though more in the formats of jazz fused with classical and religious music. The best known of these works is the cantata Ethiopia. Matthews was also active in challenging segregation laws and any other areas where race equality was challenged.

Having left ragtime and blues behind long ago, Artie and Anna made great strides in encouraging new black musicians and composers throughout their tenure with the school. They are shown in the 1930 census around the corner from their campus, both listed as musicians working at the school. However, Anna died shortly after that on July 25, 1930, leaving Artie a widower. On April 10, 1931, Artie's work made it to Carnegie Hall when the song Who Am I? was performed there by black baritone Jules Bledsoe, opening the program of classical works and spirituals. By the late 1930s and well into the 1940s, Matthews was co-hosting major music festival performance each summer with the June Festival Chorus and Coccunity Chorale, including one concert in 1942 featuring famed baritone Paul Robeson.

In 1938 Artie received an honorary doctoral degree from Central State University as acknowledgement of his great community service. In the 1940 census he is shown as widowed and living at their home school, his occupation now shown as music teacher in his home studio, assumed to still be the Cosmopolitan School, where he may have had living quarters by that time. In 1941 he became director of the Black-centric Carmel Presbyterian Church and Community Center. Somehow he was not enumerated for the 1950 Federal Census. However, Artie did eventually remarry to the widow Hazel V. Langley Anderson in early 1951, 33 years his junior, acquiring her four children from her prior marriage in the process, including Ronald, Jewell, Reginald and Andre. They would add one more when Artie Matthews, Jr., was born on December 4, 1951. Among his other important roles in the Cincinnati music community was as the secretary and treasurer of the Cincinnati Musicians Local 814 union.

Artie Matthews lived long enough to have heard some of his Pastimes played by Wally Rose with the Yerba Buena Jazz Band in the early to mid 1940s, and a well-regarded 1952 rendition of his Pastime Rag #3 performed by Barbary Coast Paul Lingle on the new Good Time Jazz label, part of the great 1950s ragtime revival. He continued to teach at his home and school until his death, which was just short of his 70th birthday. Services were held at the Calvary Methodist Church where he commanded the organ on Sundays for two decades.

Dr. Artie Matthews' musical and personal legacy goes far beyond the Pastime Rags, and it is hard to judge how much of a ripple effect he had on black music and musicians in the United States. His legacy now includes the work continued by his soon Art Matthews who is also an accomplished traditional and electronic musician and teacher. Still, the Pastime Rags and his arranged rags remain as among the finest works of the Ragtime Era, and rate (especially with this author) as works equal to those of the other three greats, Scott Joplin, Joseph Lamb and James Scott.

I would like to add a personal note of thanks to the late Art Matthews (d.1/15/2022), Artie's son, who helped me obtain information and materials in relation to his extraordinary father. Thanks also to researcher Dave Lewis of Cincinnati (formerly with All Music Guide) who sent along a couple articles on Matthews from local newspapers. The remaining information was taken from public records and periodicals or newspapers.