Muriel Pollock (sometimes seen as Pollack) was a first-generation American, the daughter of Russian immigrants Joseph Pollock and Rose Graff. She was born Mary Pollock in Kingsbridge, New York, the oldest of three siblings, including Robert (2/11/1896) and Ruth (11/22/1906). As of 1900 the family was living in Bronx, New York, with Joseph working as a news butcher. In the 1905 New York State census he was listed as a clothing manufacturer, but soon went back into newspapers. By the early 1910s, Mary started going by Muriel, which may have been her middle name. Her nickname was Molly, used more commonly in her later years.

In the 1905 New York State census he was listed as a clothing manufacturer, but soon went back into newspapers. By the early 1910s, Mary started going by Muriel, which may have been her middle name. Her nickname was Molly, used more commonly in her later years.

In the 1905 New York State census he was listed as a clothing manufacturer, but soon went back into newspapers. By the early 1910s, Mary started going by Muriel, which may have been her middle name. Her nickname was Molly, used more commonly in her later years.

In the 1905 New York State census he was listed as a clothing manufacturer, but soon went back into newspapers. By the early 1910s, Mary started going by Muriel, which may have been her middle name. Her nickname was Molly, used more commonly in her later years.When Muriel was still at a young age, musician Henry B. Harris recognized her unique musical talents, and helped her to obtain a musical education at the New York Institute of Musical Art (later known as the Juilliard school), focusing on harmony and performance. As Robert also became a working pianist in the 1910s, it is possible he attended the same school. Muriel helped support herself in school by playing in Manhattan movie houses both as pianist and orchestra leader, and working her father's newspaper stand at the Far Rockaway, New York, train station. In 1914 Muriel teamed up with Mrs. Marie Wardall to write a musical comedy, Mme. Pom Pom. It was debuted on her 19th birthday (although she claimed 17th for the newspapers) and actually had a great deal of local support, as noted in this 1914 review:

Miss Muriel Pollock, a recent high school graduate, who not only takes but gives music lessons, leads an orchestra in a moving picture theatre and in her spare moments tends her father's news stand in Far Rockaway, made her debut last night as a composer of musical comedy before an audience that crowded the ballroom of the Far Rockaway Club. It was an important night in this busy young woman's career as, coincident with her "arrival" as a composer, she celebrated her seventeenth [sic] birthday.

The collaborator with Miss Pollock was Mrs. Marie Warbell [sic], who furnished the book and some of the lyrics. Mr. Isidor Witmark [a son of music publisher M. Witmark] led the orchestra of twenty-six musicians, and Mr. James W. Castle was the stage manager.

The music comedy, called "Mme. Pom Pon," [sic] told a lively story in two acts of the experiences of twenty-six young men and women at a fashionable resort in Florida, and in the telling the company sang constantly and well and danced upon the slightest provocation.

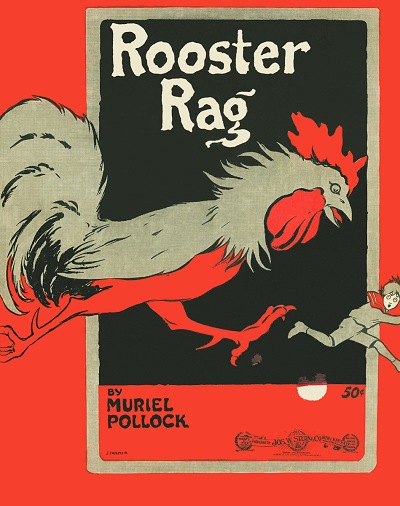

Muriel would write a few other works with Marie Wardall, but they would not be copyrighted or published until the late 1910s. Later in 1914 she debuted the work Carnival at a carnival held to support the Sanitarium for Hebrew Children in Rockaway Park, leading a band in the work. Over the next couple of years Muriel continued to work in the movie houses, but also made an effort to break into music either via Broadway shows or music publishers. Among the pieces she composed in that period was her iconic Rooster Rag, which is still popular a century later. The rag's originality is slightly suspect in that the opening of the A section is a relatively direct quote of Missouri composer Artie Matthews' Pastime Rag #1, but it becomes more original in the later sections.

Muriel eventually did make incursions into professional music, but it was through another popular media form of the time. By 1917, she was part of the piano roll recording and editing staff for the Rythmodik Music Corporation, a branch of Ampico. She was shown as employed as a music composer by Rythmodik in the January, 1920, enumeration, but living across the river in Closter, New Jersey still residing with her family. When the focus of Ampico shifted away from the Rythmodik line around mid-1920 she moved to the Mel-O-Dee Music Company. Muriel's roll recordings showed how adept she was in the interpretation of works by novelty writers, but her early work was more focused on editing the playing of others, fashioning ideal performances. There was an interesting account of her piano roll work by writer Robert A. Simon published in a May 1920 edition of The New York Evening Post:

"The most remarkable thing about player pianos," recently commented a man who owns one, "is the fact that famous pianists are able to make hand-played rolls of their best numbers without a mistake. Aren't they nervous when they record for posterity? Or do they forget about temperament and rattle off a flawless performance for the machine?"

There are several reasons why hand-played rolls fail to reveal the "blue" notes, which sometimes drop from the most magical fingers. One of the best reasons is Miss Muriel Pollock, whose job it is to edit recordings for a large player-piano house. Editing isn't Miss Pollock's only calling; she admits that she herself has made a recording of "Dardanella" and that sometimes she composes. Take it either way, she is a specialist in "blues," whether she eliminates them or immortalizes them on the perforated paper.

"My troubles start where the player's leave off," explained Miss Pollock in her little cubbyhole in the recording studios. "When a famous pianist like Rachmaninoff or Mischa Levitski comes to play for us he goes into a room with a recording piano. There he plays all by himself, and the roll tells the rest."

|

The pianist having performed, as he thinks, to his satisfaction, the master roll passes into the hands of Miss Pollock. "Some artists, like Rachmaninoff, for instance," said Miss Pollock, "never strike a false note. But some equally celebrated pianists make master records that might be put on the market as the 'Virtuoso Blues' or something like that. Last week we played a master roll for a famous musician and he swore that his bitterest enemy had made the record. He refused to believe that it was his own work."

Miss Pollock, however, soothes the irate genius by cryptic red and black pencilings on the master roll, after which an equally cryptic mechanical process removes the "notes that are sweeter unheard.

"Don't you think that a pianist is entitled to a few 'blue' notes when he plays rolls?" I suggested, "knowing that future generations will judge him by what passes between him and the piano alone in that little recording room?"

'"They aren't always alone," replied Miss Pollock, "although most of them prefer to record without company. There's one woman, whose fame extends beyond their piano playing, who feels that she performs better when she carries with her the contents of several bottles of expensive, not to say far-reaching, perfume. And then there's a young pianist who likes to be accompanied on a second piano, with some one beating time for him. One great symphonic conductor broke a lovely new baton the other day while we were recording a concerto."

However, concert pianists are not so eccentric as the folk who make the dance rolls. "Rag players are the most temperamental," said Miss Pollock. "Even the women players of classic music are less emotional than the jazz artists. I know of one fox-trot exponent who would like to play in evening clothes to give class to his offerings. Concert pianists worry about shading and expression, but jazz players worry about soul. There are enough souls floating about loose when there's a blues recording going on to supply most of the ouija boards in town."

Although world-renowned musicians hover constantly about Miss Pollock's studio, her greatest thrill came not so many years ago when she started her musical career as a pianist in a movie house somewhere on Long Island. "I was only a kid then," she reminisced, "and one night, between shows, a man came down to the piano and said: 'You played that last piece better than any one I ever heard and I ought to know because I wrote it'."

Miss Pollock strummed a few bars on her piano. "Do you recognize it?" she asked. It was "Waiting for the Robert E. Lee."

"Who are the celebrities whose rolls you have laundered?" I inquired. Miss Pollock reeled off a list that sounded like the musical "Who's Who?" "But don't mention all these names," she implored, "because they might get excited, and the next time they played for us [there would] be so many blue notes that I mightn't be able to catch all of them — and then posterity might blame the pianist instead of me."

Throughout her career Pollock collaborated with a number of lyricists, creating both popular songs and stage musicals. Some of the first notices of Muriel playing for public concerts were found in 1920.  In 1923 Muriel had two of her pieces interpolated into the Broadway show Jack and Jill, which ran for 92 performances. From the late 1920s to early 1930s, while still in New York, Muriel teamed up with pianist Constance Mering on the radio for a number of vivacious duets. They also cut several rolls for the Duo-Art label. Advertisements of 1925 and later show the name of another partner, Vee Lawnhurst (born Laura Lowenherz and often shown as V. Lawnhurst) as well.

In 1923 Muriel had two of her pieces interpolated into the Broadway show Jack and Jill, which ran for 92 performances. From the late 1920s to early 1930s, while still in New York, Muriel teamed up with pianist Constance Mering on the radio for a number of vivacious duets. They also cut several rolls for the Duo-Art label. Advertisements of 1925 and later show the name of another partner, Vee Lawnhurst (born Laura Lowenherz and often shown as V. Lawnhurst) as well.

In 1923 Muriel had two of her pieces interpolated into the Broadway show Jack and Jill, which ran for 92 performances. From the late 1920s to early 1930s, while still in New York, Muriel teamed up with pianist Constance Mering on the radio for a number of vivacious duets. They also cut several rolls for the Duo-Art label. Advertisements of 1925 and later show the name of another partner, Vee Lawnhurst (born Laura Lowenherz and often shown as V. Lawnhurst) as well.

In 1923 Muriel had two of her pieces interpolated into the Broadway show Jack and Jill, which ran for 92 performances. From the late 1920s to early 1930s, while still in New York, Muriel teamed up with pianist Constance Mering on the radio for a number of vivacious duets. They also cut several rolls for the Duo-Art label. Advertisements of 1925 and later show the name of another partner, Vee Lawnhurst (born Laura Lowenherz and often shown as V. Lawnhurst) as well.In 1925 Muriel made her first foray into marriage. There were red flags from the start, and it eventually failed, but it was announced in November of 1925 that she had married Professor Leon Leroy Groll of Pelham Manor, New York on October 15. Groll was an Austrian immigrant born in 1878 who was known as a Physical Culture Instructor, analogous to a personal trainer. He also worked as an ice skater, acted in early films, and soon became an expert equestrian and riding instructor as well. In 1915 he was the co-respondent in a divorce case concerning Mabelle M. Lane, in which he had allegedly kissed and made other advances to her while her daughter, Gertrude, stood outside holding their horses. Mr. Lane was soon granted his divorce. In a strange twist, Groll ended up marrying their daughter Gertrude in 1917 when he was 36 and she was just 18. Both parents were in attendance that day.

His first marriage having dissolved in the early 1920s, Groll then went after Muriel. They settled at his Pelham Manor equestrian facility where she continued to compose and perform, albeit keeping her professional and maiden name of Pollock.

In 1926 Muriel advertised "Instruction in Piano," saying she would "accept a limited number of pupils," giving Grolls's Riding Academy as her address. The last mention of Muriel in respect to Leon was in 1927. The timeline becomes murky here, but it is apparent that she left the marriage before 1930, and was not found in that enumeration, nor was Leon. He married once more, and divorced once more, finally committing suicide in 1962 in order to escape some bodily pain he was experiencing.

|

Keeping up with her professional life, Muriel and Constance were featured nightly in the musicals Rio Rita (1927-1928) and Ups-a-Daisy (1928) on Broadway, a time during which two piano teams like Victor Arden and Phil Ohman were big draws in the theaters. The following year, Pleasure Bound, a stage musical that she wrote much of the music for, had a fairly decent run of 136 performances before closing. She allegedly wrote many more musicals, but this is the only one known to have been produced on Broadway. Pollock and Mering continued to sparkle with their inimitable style over the radio into the late 1920s, but Lawnhurst's name started to show up with increasing frequency as her alternate partner, and Mering's faded at the same time due to illness from tuberculosis in 1930.

In addition to her dynamic piano performances, Muriel was becoming known as a skilled organist, and would often focus on theater organs for her later appearances on radio. More importantly, she believed in the power of radio broadcasts and felt that they could be even better utilized for the dissemination of culture and music. In an effort to prove this, under the sponsorship of the Palmolive Company and director Gustave Haenschen, she composed a suite of Spanish-themed pieces in 1929, debuting the first of them, Dance Espanol, exclusively on the Palmolive program on NBC. In Muriel's own words came a fairly accurate assessment of the future of the medium:

I firmly believe that the time has come for radio to demand its own special form of music and that many such compositions from now on will first reach the ears of the public via the air. To my mind radio demands a special technique of the composer just as it does of the musician and the vocalist and that the finest music of the air will be written specially for it with a clever understanding of the musical requirements of the broadcast studio. In addition to meeting with these requirements the composers will have the thrill of presenting their work to a nation-wide audience for the first time via the air.

On June 23, 1933, Muriel was married to William "Will" John Donaldson, a songwriter who had co-written Rialto Ripples with Gershwin, and also worked for the Rythmodik branch of Aeolian as a staff artist and producer. The 1930 census showed him as having married in 1926 but living alone in Manhattan. A 1934 article indicates that his first wife, Josephine Plant, had just lost a sixteen-week battle with illness. So it appears that even though she was pregnant with Will's child in 1933 that Josephine had already dissolved that union, possibly due to Muriel. Pollock's last known contribution to the Great White Way would be in Shoot the Works in 1931, which included a hodgepodge of pieces by composers as diverse as George Gershwin and Irving Berlin. Muriel became a member of American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1933.

Even before Constance Mering's untimely death in 1933, Pollock was playing duets almost exclusively with Vee Lawnhurst, usually for NBC. Often billed as the Ladybugs, and later the Lady Fingers (after a New York columnist applied the term Lady Bugs to effeminate young men in early 1932), these New York radio fixtures continued their run of creating hot duets on both radio and record, and some of their broadcasts were being syndicated around the country. Vee was turning into a fine composer as well, contributing music for interpolation into some Broadway revues. Muriel was showing up frequently from 1929 on as a solo artist on programs with widely varying content, often a mix of popular classics and popular songs. She even played one piano roll duet with George Gershwin, the Aeolian version of Make Believe.

Often billed as the Ladybugs, and later the Lady Fingers (after a New York columnist applied the term Lady Bugs to effeminate young men in early 1932), these New York radio fixtures continued their run of creating hot duets on both radio and record, and some of their broadcasts were being syndicated around the country. Vee was turning into a fine composer as well, contributing music for interpolation into some Broadway revues. Muriel was showing up frequently from 1929 on as a solo artist on programs with widely varying content, often a mix of popular classics and popular songs. She even played one piano roll duet with George Gershwin, the Aeolian version of Make Believe.

Often billed as the Ladybugs, and later the Lady Fingers (after a New York columnist applied the term Lady Bugs to effeminate young men in early 1932), these New York radio fixtures continued their run of creating hot duets on both radio and record, and some of their broadcasts were being syndicated around the country. Vee was turning into a fine composer as well, contributing music for interpolation into some Broadway revues. Muriel was showing up frequently from 1929 on as a solo artist on programs with widely varying content, often a mix of popular classics and popular songs. She even played one piano roll duet with George Gershwin, the Aeolian version of Make Believe.

Often billed as the Ladybugs, and later the Lady Fingers (after a New York columnist applied the term Lady Bugs to effeminate young men in early 1932), these New York radio fixtures continued their run of creating hot duets on both radio and record, and some of their broadcasts were being syndicated around the country. Vee was turning into a fine composer as well, contributing music for interpolation into some Broadway revues. Muriel was showing up frequently from 1929 on as a solo artist on programs with widely varying content, often a mix of popular classics and popular songs. She even played one piano roll duet with George Gershwin, the Aeolian version of Make Believe.Will's wife Josephine gave birth to their son, Theodore (Ted) Donaldson, in August of 1933. She died soon after, and Ted went to live with some of her family members until he was five. Muriel and Will appear to have remained in New York through the early 1940s, although Donaldson had made some excursions to Hollywood, California, largely as an arranger for films. The couple and Teddy were found living temporarily in midtown Manhattan for the 1940 census, both listed as musicians working in broadcasting. Will was still in Manhattan for the 1942 draft as well.

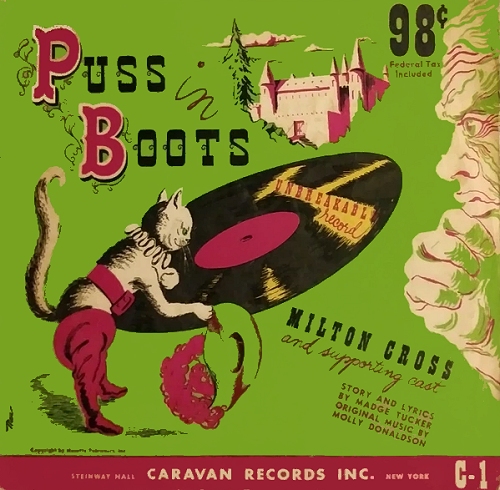

Muriel worked to reinvent herself again in the late 1930s, this time writing short radio musicals for children, many of which were broadcast in syndication from 1940 into the early 1950s. Most of those in the early 1940s were written with Madge Tucker ("The Lady Next Door"), NBC's director of children's programming. Some were also reduced in size to accommodate children's record sets. During this time she often wrote under the name Molly Donaldson. Also, selected compositions for children's piano books were composed with her son Ted. With Will she wrote The Boys and Girls Quiz Book in 1940.

When Pollock and Donaldson moved to California in the early 1940s, Muriel, now without Lawnhurst as her playing partner, was unable to retain the popularity that she had sustained in New York. Her solo broadcasts on NBC continued, often as a guest artist on popular programs and more on organ than piano. Some were from California and some were done from New York when she could get there. Muriel eventually faded from public view. Her husband continued working as a composer and arranger on both coasts throughout the late 1940s, in both recording and movie studios. Their son, Ted, had been acting since he was four on stage, radio, and in some movies as a talented child performer. His big screen debut was with Cary Grant in 1943 in the film A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. The family lived at 1422 N. Alta Vista Blvd., just south of Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood, throughout most of the 1940s and 1950s.

Having some difficulty in maintaining steady work in her fifties, Muriel more or less retired by 1950. The 1950 enumeration showed no occupation for her, while Will was teaching in a voice studio, and Ted was regularly acting in radio shows. Will Donaldson, died in 1954. On July 1, 1955, Muriel and Ted donated the Will Donaldson Collection of Theodore Drieser Books and Manuscripts to the UCLA Special Collections Department.

Muriel lived in Hollywood until her death at age 76. She bequeathed a twin stone diamond ring to Los Angeles City College, where she had furthered her education as a student in the late 1950s, for the purpose of establishing a scholarship. The ring was auctioned off in January, 1973, and started a liberal arts scholarship in her name. In the 1990s, musician Artis Wodehouse resurrected a number of fine piano rolls by Muriel and others in a MIDI format that allowed for enhanced expression on a Yamaha grand, once again bringing life to a performer who herself gave life to many great pieces during her career.

Compositions

Compositions